Mushrooms

The New Moon grows mushrooms and the Old Moon shrinks them. It is also said that it loses them.

Noor kuu kasvatab seeni, vana kuu kahandab, ööldakse ka: kautab.

In order to destroy flies, a fly agaric was brought from the forest. It was fried, and sugar was sprinkled on top.

Selleks, et hävitada kärbseid, toodi metsast kärbseseen, praeti see ja riputati suhkrut peale.

In order to stop bleeding, yarrow water and puffball can be used.

Achillea millefolium; Lycoperdon perlatum.

The puffball is called with it's vernacular name 'mother-in-law's fume' here.

Verejooksu kinni panemiseks saab raudvere-rohu vett ja ämmatossu tarvitatud.

Harilik raudrohi ja murumuna.

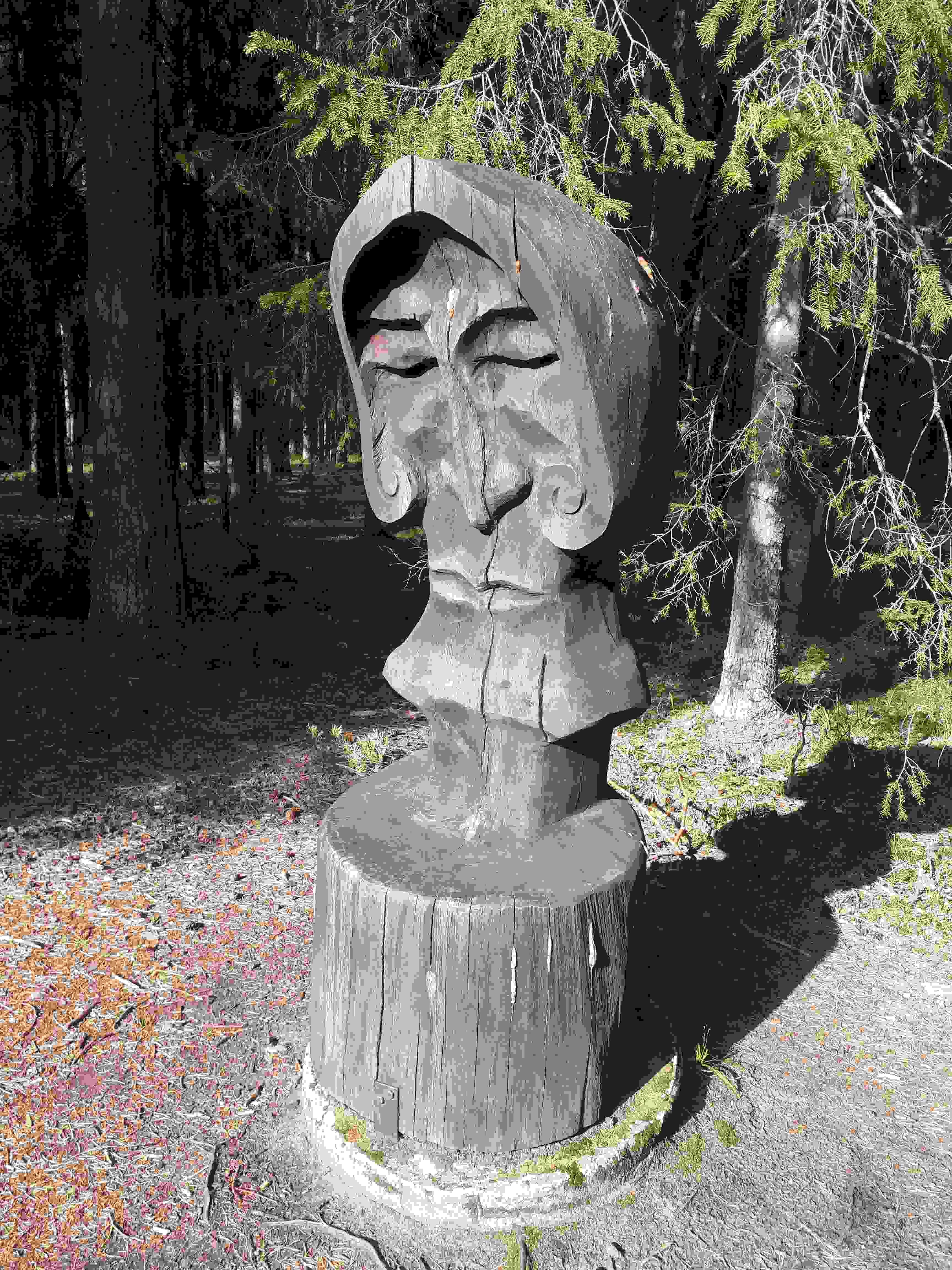

Once upon a time some men out hunting for mushrooms in the forest found one that was bigger than any they had ever seen before. They began pulling it out of the ground when—a little old man sprang out from underneath it. He was no larger than a finger with a beard twice his size. The little old man rushed off, but the men ran after him. They caught him and asked who he was. Said the little old man:

"I am king of all the mushrooms growing in this forest."

The men did not know what to do. They thought and they thought and could think of nothing better than to give the little old man for a gift to the king. This they did and the king rewarded them generously and ordered the little old man to be locked up in the cellar.

"I shall hold a big feast," said the king to himself, "and show my guests what funny little old men live under the mushrooms in my forest. Meanwhile, he must stay under lock and key."

Now, the king had a young son. One day the boy was in the courtyard playing with a golden egg and he happened to send it rolling through a window straight into the cellar. The little old man saw the egg and snatched it up.

"Give me back my egg!" cried the boy. But the little old man called back: "I won't! Come and get it yourself." "How can I do that? The door is locked," the boy said. "That's nothing. The keys are in the palace. Go and fetch them."

The boy did as he was told, and, when he had brought the keys, he unlocked the door and came down into the cellar. The little old man gave him the golden egg, and then he dashed through between the young prince's legs and out the door and vanished. The prince, who had not noticed anything, wanted to take a good look at the little old man before locking him up again. He gazed round, and, finding the little old man gone, was badly frightened. Locking the door quickly, he took the keys back to the palace and never breathed a word to anyone about what had happened.

The day of the feast arrived and there were many from all parts of the kingdom who came to attend it. A big crowd gathered round the palace, for everyone had heard that the king had a surprise in store for his guests. The king now sent a servant of his to fetch the little old man. The servant returned empty-handed, but when he said that the little old man was not in the cellar, the king refused to believe him and climbed down himself to have a look. However, what isn't there, isn't there, and though the king felt ashamed at having called together his guests for nothing, he could not conceal from them that the little old man had vanished. He told them that he had got out of the cellar through a mouse-hole, and this they all believed and were very sorry indeed not to have seen him.

Many years passed and the young prince grew to manhood. Once at dinner the talk turned on the little old man, and the prince confessed it was because he had sent his golden egg rolling into the cellar that the little old man had managed to escape.

The king was very angry. He would not listen to anyone, not even to the queen, and drove the prince out of the palace. But a general was ordered to go along with him for company, for the king knew that it was easier for two people to roam the world together and take care of themselves.

The prince and the general set off on their way. They walked on and on, and after a time they reached a forest. It was very hot and the prince felt thirsty, but where were they to get water?

They walked on a little further, and there before them was a deep well. Said the general:

"I'll let you down into the well on a rope if you like, and, when you have drunk your fill, I'll pull you out again."

The prince agreed and the general let him down into the well, but when he had drunk his fill, the general called down to him: I'll pull you out again on one condition—that from now on you will be the general and I will be the prince."

What was the prince to do? If he refused, the general, knave that he was, would leave him in the well. There was nothing for it but to agree. The general pulled the prince out and they went on again. They came to the king of a strange kingdom and asked him if he had any work for them. And all the time they kept to their agreement: the general calling himself a prince and the prince calling himself a general. The king took the sham prince into the palace with him and he made the real one his chief groom. The other grooms drove the horses to pasture in the forest and the prince went with them, for it was his job to watch over them.

The prince sat down on a rock and he sorrowed and grieved over his sad plight. All of a sudden there stood before him the self-same little old man whom he had let out of the cellar all those many years ago.

"Why are you so sad?" asked the little old man.

Said the prince in reply: "There is no reason for me to be happy. My father drove me out of the palace because I let you escape and now the general has taken over my title. He calls himself a prince and I am obliged to pasture horses."

"Don't you grieve, everything will turn out all right, the little old man said, trying to comfort him. "Come with me to my eldest daughter's palace."

Now, this made the prince very curious. "Who are you, then?" he asked. The little old man said: "They call me the King of the Mushrooms, for I am the oldest and wisest of them."

And he led the prince to his eldest daughter’s palace. The palace and everything in it was made of copper, and it was truly a place to fill one with wonder! So happy did the prince feel there that he did not notice how the hours passed.

"It is time for you to leave us now," said the King of the Mushrooms, "but, as it is our custom, we will give you a farewell present. Hey there! Bring in a copper horse!" A copper horse was led in, and so spirited was he that it took four men to hold him.

"This is my present to you," said the King of the Mushrooms. The prince was frightened. "What will I do with him? Why, it takes four men to hold him!" said he. But the King of the Mushrooms replied: "Here are four bottles of my magic potion. Drink it if you want to be strong!"

The prince drank the potion and at once felt so strong that he feared the copper horse no longer. Then the King of Mushrooms gave him a copper pipe and said: "Take good care of this pipe. If you lose it you will lose your horse too. Now put on the copper armour that is under the saddle." The prince put on the armour, mounted the copper horse and rode off at a gallop.

On the following da when he went to the forest to graze the horses he met the King of the Mushrooms again. "Today you’ll have to pay a visit to my middle daughter," he said. The prince mounted his copper horse and made off at a gallop for the middle daughter's palace. Now, the middle daughter's palace was a silver one and everything in it was made of silver. Time passed quickly, and the King of the Mushrooms had a silver horse brought for the prince as a farewell present. Eight men held the horse and it was almost more than they could manage, so how could one man expect to cope with him? The King of the Mushrooms told the prince to drink eight bottles of his magic potion. This the prince did and then he took the silver armour from under the saddle. He put it on and all of him sparkled and shone. And then the King of the Mushrooms brought out a silver pipe from his pocket.

"Take good care of it or you'll lose your horse," said he.

On the third day the prince went to visit the youngest daughter of the King of the Mushrooms who lived in a palace of gold. There the King of the Mushrooms gave him a golden horse for a present and it took twelve men to hold him. The prince had to drink twelve bottles of the magic potion before he grew strong enough to cope with the horse.

The King of the Mushrooms gave him a golden pipe and said to his daughter: "You too must give our guest a keepsake."

The youngest daughter brought a golden egg and gave it to the prince, who thanked her, got on his golden horse and galloped away.

He came back to his grooms and on the following day went to see the king in whose service he was. On his way there he saw the king's youngest daughter. She came running out of the palace and was weeping loudly. "What has happened? Why are you crying?" the prince asked.

And the princess replied: "How can I help it! Tomorrow a terrible dragon is going to crawl out of the sea and eat me up. If they don't give me to him he will destroy the whole kingdom." The prince took pity on the princess.

On the following day, when the king's soldiers had lined up on the coast and the princess arrived and stood waiting for the dragon, he went to the forest and blew his copper pipe. At once the copper horse appeared before him, and the prince put on his copper armour, got on the horse and made off at a gallop for the sea.

Now, it was just about then that the dragon crawled out of the sea on his four paws.

"Is there anyone among you brave enough to fight me?" he asked the people gathered on the shore.

No one replied and they all stood there in silence. Just then the prince arrived, riding up to the dragon on his copper horse.

"Who are you going to fight for?" asked the dragon.

"For the princess and myself," the prince replied.

"How are you going to fight—on horseback or on foot?" asked the dragon again.

"On horseback," the prince said. "After all, you have four legs, too, like my horse."

The dragon decided to use cunning. He ran off at first but then turned round very suddenly, thinking to swallow the prince whole together with his horse. But this was not to be!

The prince caught up with the dragon, smote off his head with a single wave of his sword, threw his body into the sea and galloped off toward the forest. But not a word did he say to his grooms, just as if nothing had happened.

On the following day the prince went to see the king again, and there, coming out of the palace, was the king's youngest daughter, weeping loudly.

"What has happened?" asked the prince. "Why are you crying?"

And the princess replied: "Tomorrow a six-headed dragon is going to crawl out of the sea and eat up my elder sister. How I wish I could find the brave man who saved me, for he would save my sister too!"

The prince returned to the forest, and on the following morning he blew his silver pipe, and at once the silver horse appeared before him. The prince put on his silver armour, mounted the horse and galloped away. He rode up to the sea and waited for the six-headed dragon. All of a sudden the sea boiled up, and the six-headed dragon crawled out of the water and called on the bravest among the men gathered there to fight him. All the soldiers ran off helter- skelter, and only the prince on his silver horse made straight for the dragon.

"That's right, my son, come closer!" called the dragon. "It will be all the better for me, for I will eat you both!"

And the dragon opened wide his jaws, thinking to swallow the prince together with his horse. But the prince's sword flashed, and all of the dragon's six heads rolled down on to the sand like ordinary heads of cabbage.

The prince returned to the forest just as if nothing had happened, let his silver horse go and went off to have a sleep.

The following day on his way to the palace he met the youngest princess in tears again. "What has happened now?" asked the prince. And the princess replied:

"Tomorrow a twelve-headed dragon is going to crawl out of the sea and eat up my eldest sister. How I wish I could find the brave man who saved me and my other sister!"

The prince took pity on the girl, and when morning came he blew his golden pipe. The golden horse appeared before him, and the prince put on his golden armour, got on the horse and made off at a gallop towards the sea.

The eldest princess was already on the shore waiting for the twelve-headed dragon, and the king was there too with his soldiers, for he wanted to see how his daughter would fare. After a time there came the most fearful noise, the sea began to seethe and to boil, and the twelve-headed dragon thrust all his twelve heads out of the water and then crawled out onto the shore. The soldiers ran off in fright, the king took to his heels and only the prince on his golden horse galloped boldly straight for the dragon. The dragon saw him and began to mock and to jeer at him.

"That's right, my son, come closer!" he cried. "It will be all the better for me, for I will eat up both you and your horse!"

And, thinking to swallow the prince, the dragon opened wide his jaws. But the prince waved his sword and six of the dragon's heads rolled to the ground like heads of cabbage. At this the dragon flew into a rage and began threshing the prince and his horse with his tail. Smoke poured from the dragon's mouth and steam from his nostrils and he was about to swallow his victim when suddenly the prince saw the King of the Mushrooms standing before him on a large rock.

"Make haste and crack the golden egg!" he called.

The prince took the golden egg from his pocket and broke it in two, and at once a whole host of warriors poured out of it and attacked the dragon fearlessly. The dragon stood gaping at them, and the prince made good use of this and with one wave of his sword smote off his six remaining heads. The dragon fell lifeless to the ground.

Then the prince took out the two halves of the golden egg, and the warriors at once poured back into it. The dead dragon was left on the beach, and the prince galloped off into the forest and slept there for three days and three nights.

On the fourth day he felt someone shaking him, and when he opened his eyes, he saw the King of the Mushrooms standing beside him.

"Get up quickly and go to the king, said the King of the Mushrooms. "That knave of a general of yours is there, demanding that the princess be given him in marriage. He says that it was he who killed the three dragons."

The prince jumped up and blew his copper pipe. The copper horse appeared and the prince put on his copper armour and made off at a gallop for the palace. He reached it in no time and there he saw the general standing beside the king and boasting about how he had vanquished the three dragons.

The youngest daughter saw the prince and was overjoyed.

"Look, father, there is my true saviour!" she cried.

But the prince turned his copper horse round and rode off into the forest. There he blew his silver pipe, got off the copper horse and on the silver one and rode back to the king's palace. The middle daughter saw him and cried:

"Look, father, there is my true saviour!"

But the prince turned round his horse and rode off into the forest. There he blew his golden pipe, and, getting off his silver horse and on the golden one, made for the king's palace. The eldest daughter saw him and cried:

"Look, father, there is my true saviour!"

The prince was about to ride back to the forest again but the king stopped him and invited him into the palace that he might reward him for having saved his daughters.

"We have a prince from a far-off land here who says that he saved my daughters," said the king.

"I don’t know why they call you their true saviour."

"The man who is passing himself off as a prince is only one of my generals," the prince said.

The king was much surprised.

"Then it is you who is the prince?" said he. "Well, then, you shall be richly rewarded for your valour. And you can take any one of my daughters in marriage besides. Just choose the one you like."

But the prince thanked the king, and, saying that there was nothing he needed, galloped off into the forest without waiting for his reward. The king stood looking after him, and then came back to his palace and drove out the general.

And as for the prince, he now made straight for the golden palace where the youngest daughter of the King of the Mushrooms lived. They were married and lived together happily ever after. But as for the King of the Mushrooms, from that day on no one laid eyes on him again.

Vanasti läinud seenelised metsa seenele. Leidnud suure seene, tõmmanud maast üles. Seene alt tulnud sõrmepikkune vanamees välja, vaksa pikkune habe enesel. Vanamees punuma. Seenelised järele. Saavad vanamehe kätte. Küsivad, kes ta on. Vanamees vastu:

„Mina valitsen nende seente üle, mis siin metsas kasvavad!”

Seenelised peavad nõu, mis väikse vanamehega teha. Arvavad viimaks kõige paremaks väike vanamees kuningale kingituseks viia. Viivadki kuningale. Kuningas maksab seenelistele ausasti vaevapalka. Väikse vanamehe aga laseb keldrisse kinni panna.

Kuningal tahtmine suurt võõruspidu teha ja võõrastele seene alt leitud meest näidata. Seni tahab väikse vanamehe keldris kinni pidada.

Kuninga väike poeg läinud õue peale kuldmunaga mängima. Mängides kukkunud kuldmuna kuningapoja käest keldri aknast sisse. Kukkunud just sinna, kus väike vanamees vangis olnud. Väike vanamees võtnud kuldmuna, näidanud läbi akna poisile.

Poiss hüüdma: „Anna muna siia!” Väike vanamees vastu: „Siis saad, kui ise siia mu juurde tuled!” Poiss küsima: „Kuidas ma su juurde saan? Uks on lukus!” Vanamees vastu: „Mine too toast võtmed!”

Poiss läheb, toob toast võtmed. Avab keldri ukse, astub sisse. Vanamees annab poisile kuldmuna kätte, kargab aga ise lipsti poisi jalgade vahelt läbi uksest välja. Poiss ei näegi, kuidas vanamees oma teed läheb. Poiss hakkab ust kinni panema. Vaatab enne, kas vanamees seal. Ei vanameest kusagilgi. Poisil suur hirm südames. Keerab ukse lukku, viib võtme tagasi. Ei räägi kellelegi, et keldris käinud ja et väike vanamees ära põgenenud.

Pidupäev jõuab kätte, mil kuningas pisikest vanameest lubab näidata. Tuleb piduvõõraid, tuleb rahvast hulgakaupa kokku imet vaatama. Kuningas saadab toapoisi väikest meest keldrist ära tooma. Toapoiss tuleb tagasi, ütleb kuningale salaja kõrva sisse, et väike mees kadunud. Kuningas ei taha uskuda. Läheb ise vaatama. Aga mis kadunud, see kadunud. Ei aita, kuningal küll häbi, et piduvõõraid ninapidi vedanud, aga peab võõrastele viimaks ometi kuulutama, et väike mees kadunud. Kuningas avaldab arvamist, et väike mees kuidagi hiireaugust välja pääsenud ja ära põgenenud. Piduvõõrad ja rahvas jäävad seda juttu uskuma. Kahetsevad väga, et pisikest meest näha ei saa.

Aastad lähevad mööda. Kuningapoeg kasvab meheks. Korra tuleb söögilauas jutt väiksest mehest. Kuningapoeg räägib nüüd isale esimest korda, kuidas ta kuldmuna keldrisse kukkunud, ta muna välja tooma läinud ja sel teel väike mees ära kadunud.

Kuningas vihastub poja üle. Vihastub nii, et käsib pojal enese juurest ära minna. Ema palub poja eest. Aga ei kuningas hooli ta palvetest. Niipalju paneb ometi emanda palveid tähele, et pojale kindrali seltsiliseks kaasa annab. Kindraliga seltsis peab kuningapoeg maailma minema enesele peatoidust otsima.

Kuningapoeg läheb kindraliga tüki maad edasi. Jõuavad ühe metsa vahele. Ilm palav. Kuningapojale tuleb janu. Kust vett saada? Näevad kaevu. Kaev aga sügav, ei saa vett kätte. Kindral kuningapojale ütlema:

„Ma lasen su nööriga kaevu põhja.Seal võid nii palju juua, kui tahad. Pärast tõmban jälle üles! ”

Kuningapoeg nõus. Joob kaevu põhjas janu täis. Korraga kindral ülevalt ütlema: „Muidu ma sind välja ei tõmba, kui sa ei luba mind kuningapojaks ja ennast kindraliks hüüdma hakata!”

Mis kuningapojal hädas teha? Ei luba ta kindrali tahtmist täita, jätab kindral ta kaevu. Ei aita muud, kui lubab täita, mis kaval kindral nõuab. Kindral tõmbab kuningapoja kaevust välja. Mõlemad rändavad nüüd edasi teise riigi kuninga juurde. Lähevad kuningalt teenistust otsima. Kindral ütleb, et ta kuningapoeg on, ja kuningapoeg, et kindral. Kuningas võtab kindrali oma lossi, kuningapoja aga paneb oma hobusemeeste ülemaks. Hobused aetakse metsa sööma, vahid pannakse juurde. Kuningapoeg peab vahtide järele vaatama.

Kuningapoeg istub metsas kivi otsa maha. Hakkab oma kurba lugu järele mõtlema. Korraga näeb ta: seesama väike vanamees seisab ta ees, kelle ta lapse põlves keldrist lahti päästnud.

Väike vanamees küsima: „Miks nii mures oled?”

Kuningapoeg vastu: „Miks ei peaks ma mures olema!

Isa ajas mind enese juurest ära, sest et ma sul lasksin

ära põgeneda. Nüüd riisus kindral veel mu nimegi ära. Nimetab ennast kuningapojaks, mina aga pean siin hobuseid hoidma!"

Väike vanamees kuningapoega trööstima: „Ära kaeba! Küll käsi hakkab sul veel hästi käima! Tule täna mu vanema tütre juurde võõraks!”

Kuningapoeg küsima: „Kes sa siis õige oled?” Väike vanamees ütlema: „Inimesed hüüavad mind seenekuningaks, sest et ma seente üle valitsen!”

Seenekuningas viib kuningapoja oma vanema tütre juurde. Vanem tütar asub vasklossis. Kõik asjad ses lossis vasest. Kuningapoeg vaatab ja imestab. Seenekuninga vanem tütar võtab kuningapoja väga lahkelt vastu. Aeg läheb hoopis ruttu mööda.

Viimaks seenekuningas ütlema: „Aeg tagasi minna! Aga külalisele tarvis midagi kinkida. Toodagu talle vaskhobune siia!” Sedamaid tuuakse vaskhobune kuningapoja ette. Neli meest hoiavad vaskhobust kinni.

Seenekuningas kuningapojale ütlema: „Selle hobuse kingin ma sulle!” Kuningapoeg kartes vastu: „Kuidas ma sellest hobusest jagu saan? Neli meest jõuavad vaevalt teda taltsutada!” Seenekuningas silmapilk ütlema: „Vaata, seal on neli pudelit jõurohtu. Joo need tühjaks!”

Kuningapoeg joob tühjaks. Korraga tunneb enese hirmus tugeva olevat. Hobune ei pääse tema käest enam kusagile. Seenekuningas annab kuningapojale vaskvile. Ütleb ise: „Hoia seda vilet hoolega! Kaotad selle vile, oled hobusest ilma! Nüüd pane enesele veel vaskriided selga! Vaskriided seisavad sadulas!” Kuningapoeg paneb vaskriided selga. Kargab hobuse selga. Kuningapoeg jätab jumalaga, kihutab hobusekarja tagasi.

Teisel päeval istub kuningapoeg jälle metsas hobuste juures. Korraga näeb: seenekuningas uuesti ta juures.

Seenekuningas kutsuma: „Tule täna mu keskmisele tütrele külaliseks!” Kuningapoeg kargab kingitud hobuse selga. Sõidab seenekuninga keskmise tütre juurde. Keskmine tütar asub hõbedases lossis. Seal kõik asjad hõbedased. Kuningapoeg saadab seal aja väga lõbusalt mööda. Seenekuningas viimaks ütlema: „Aeg tagasi minna. Enne aga toodagu hõbedane hobune siia!” Hõbedane hobune tuuakse sinna. Kaheksa meest hoiavad kinni. Kuningapoeg ei jõua hobusest jagu saada. Seenekuningas ütlema: „Mine joo need kaheksa pudelit jõurohtu tühjaks! Siis saad hobusest jagu. Selle hobuse kingin sulle!”

Kuningapoeg joob. Sedamaid jõudu küll. Hobune ei pääse ta käest kusagile. Hobuse sadulas hõbedased riided. Need paneb kuningapoeg selga. Hõbedane mees valmis. Seenekuningas võtab taskust hõbevile välja, annab kuningapojale ja ütleb:

„Seda hoia hoolega! Muidu oled hobusest ilma!”

Kuningapoeg jätab jumalaga, tänab ja ratsutab oma teed hobuste juurde. Istub järgmisel päeval jälle metsas kivi otsas. Jälle tuleb seenekuningas ta juurde, kutsub noorema tütre juurde võõraks. Kuningapoeg läheb. Seenekuninga noorem tütar elab kuldses lossis, kus kõik asjad kullast. Kuningapoja aeg kulub seal väga lõbusasti ära. Seenekuningas viimaks kuningapojale meelde tuletama, et tarvis hobuste juurde tagasi minna. Enne annab seenekuningas ometi käsu: „Toodagu kuldhobune siia!” Kaksteistkümmend meest toovad kuldhobuse sinna. Jõuavad vaevalt kuldhobust kinni hoida. Seenekuningas ütleb kuningapojale: „Selle hobuse kingin ma sulle. Vaata, seal on kaksteist pudelit jõurohtu. Joo need ära, küll siis hobusega valmis saad!” Kuningapoeg joob kaksteist pudelit jõurohtu ära. Kohe tugev mis hirmus. Hobune ei pääse ta käest enam kuhugi. Hobusel kuldriided sadulas. Need paneb kuningapoeg enesele selga. Särab ja hiilgab nüüd üsna kullas.

Seenekuningas kingib veel kuningapojale kuldvile. Ütleb selle peale tütrele: „Kingi sinagi omalt poolt võõrale midagi mälestuseks!”

Seenekuninga noorem tütar toob kuningapojale kuldmuna kingituseks. Kuningapoeg tänab, istub kuldhobuse selga, sõidab hobuste juurde tagasi.

Teisel päeval läheb kuningapoeg linna. Näeb: kuninga noorem tütar tuleb lossist välja, nutab ise suure häälega. Kuningapoeg küsima: „Mis sa nutad? Mis sul viga?”

Kuningatütar vastu: „Miks ei peaks ma nutma! Homme tuleb kole mereelukas merest välja ja nõuab mind enesele. Kui ta mind ei saa, hukkab ta terve riigi ära!” Kuningapoeg trööstib kuningatütart nii palju, kui oskab.

Teisel päeval pannakse sõdurid mere äärde seisma. Kuningatütar sõidab mere äärde koledat elukat ootama. Seni läheb kuningapoeg metsa. Vilistab vaskvilet. Kohe vaskhobune vaskriietega seal. Kuningapoeg paneb vaskriided selga ja hüppab hobuse selga. Kihutab tuhatnelja mere äärde.

Juba kole madu merest väljas, neli jalga enesel all. Küsib kokkutulnud rahva käest:

„Kas on kellelgi julgust minu vastu tulla?"

Ei ükski julge minna. Kuningapoeg tormab aga vaskhobuse seljas maole vastu.

Madu silmapilk küsima: „Kelle eest sina välja astud?”

Kuningapoeg vastu: „Iseenese ja kuningatütre eest!”

Madu küsima: „Kas võitleme ratsul või mees mehe vastu?”

Kuningapoeg vastu: „Parem võitleme ratsul. Sul on niisama neli jalga all nagu minu hobuselgi!”

Madu hakkab ees jooksma. Arvab: pöörab äkki ümber ja neelab kuningapoja koos hobusega ära. Aga vale kõik.

Kuningapoeg maole järele. Lööb ühe hoobiga mao pead otsast ära, keha viskab merre. Kui madu tapetud, kihutab vaskhobusega metsa tagasi. Teeb ise, nagu ei oleks midagi sündinud.

Teisel päeval läheb jälle kuningalinna. Näeb jälle kuninga nooremat tütart nuttes lossist välja tulevat. Kuningapoeg küsima: „Mis viga?”

Kuningatütar vastu: „Homme tuleb kuue peaga madu merest välja minu keskmist õde saagiks saama! Oh oleks seesama mees siin, kes mind ära päästis! Oh tuleks ta ka mu õde ära päästma!”

Kuningapoeg läheb metsa tagasi. Teisel hommikul vilistab hõbevilet. Silmapilk hõbehobune väljas, hõbedased riided sadulas. Kuningapoeg paneb hõbedased riided selga, kargab hobuse selga, kihutab mere äärde. Kuningatütar juba mere ääres koledat elukat ootamas. Meri hakkab kohisema. Kuue peaga madu tuleb kohinaga merest välja. Kutsub enese vastu võitlema. Sõdurid jooksevad hirmu pärast ära. Kuningapoeg tormab aga hõbehobusega koleda kuue peaga mao kallale.

Madu hüüdma: „Tule aga tule, pojuke, mulle pruukostiks. Ühe lootsin saavat, saan kaks! ”

Kuningapoeg kihutab hõbehobusega tuhatnelja kuue peaga mao poole. Madu ajab lõuad laiali, tahab kuningapoega koos hobusega ära neelata. Enne aga sähvab kuningapoja mõõk. Kõik kuus mao pead langevad nagu kapsapead mereliiva peale.

Kuningapoeg sõidab hõbehobusega rahulikult metsa tagasi, just nagu ei oleks midagi sündinud. Metsas laseb hobuse lahti, läheb ise puhkama.

Järgmisel päeval sammub kuningapoeg jälle linna. Näeb jälle kuningatütart nutvat.

Kuningapoeg küsima: „Mis viga?”

Kuningatütar vastu: „Homme tuleb kaheteistkümne peaga madu merest mu vanemat õde saagiks saama. Oh oleks see mees siin, kes minu ja mu keskmise õe ära päästis. Oh et ta ka mu vanema õe ära päästaks!”

Kuningapoeg keelas kuningatütart nutmast. Läheb siis jälle metsa tagasi. Teisel hommikul vilistab kuldvilet. Varsti kuldne hobune platsis, kuldsed riided sadulas. Kuningapoeg paneb kuldsed riided selga, hüppab kuldhobuse selga, kihutab mere äärde.

Kuninga vanem tütar juba seal kaheteistkümne peaga madu ootamas. Varsti ilmub kuningaski sõjaväega. Kuningas tahab näha, mis tütrega sünnib. Juba kanget kohinat kuulda. Meri hakkab mühisema ja keema. Peagi pistab kaheteistkümne peaga elukas pea merest välja, ronib kaldale. Sõdurid põgenevad hirmuga oma teed. Kuningaski ei julge vaatama jääda. Kuningapoeg aga sõidab kuldhobuse seljas kollile julgelt vastu.

Merekoll pilkama: „Tule, tule, pojuke! Küll ma sind pruukostiks võtan! Ühe lootsin saada, kaks saan!”

Ajab lõuad lahti, tahab kuningapoega ära neelata. Kuningapoeg vajutab korra mõõgaga. Kuus kolli pead langevad nagu kapsapead maha. Aga seda agaramalt tungib metsaline kuningapojale kallale. Ei lase ratsameest sugugi enese ligi. Püüab sabaga kuningapoega ja hobust maha lüüa. Kuningapojal tegemist küllalt, et sabalöökide eest ennast eemal hoida. Kole elukas puhub suust ja sõõrmeist tulist õhku kuningapojale vastu. Kuningapoeg ei pääse enam sugugi ligi ega saa mõõgaga midagi viga teha. Peab ennast hoidma, et koll teda õnneks ei võtaks. Korraga näeb kuningapoeg: seenekuningas suure kivi ääres.

Seenekuninga hüüdma: „Kuldmuna appi!” Kuningapoeg võtab taskust kuldmuna, avab selle. Äkki ta ümber kõik kohad sõjamehi täis. Kõik tungivad igast küljest kolli kallale. Ei karda kolli sugugi! Koll hakkab neid tagasi tõrjuma. Seal tormab kuningapoeg kuldhobuse seljas uuesti koleda eluka kallale ja raiub ühe hoobiga ta kuus ülejäänud pead maha. Koll otsas korraga.

Kuningapoeg võtab jälle kuldmuna kätte, avab muna. Silmapilk suur sõjavägi kuldmuna sees tagasi. Kuningapoeg jätab metsalise sinna surnult maha ja kihutab metsa tagasi. Ei tee sest väljagi, et ta suure töö korda saatnud. Metsas heidab suure väsimuse peale magama. Magab kolm päeva ühtejärge.

Kolme päeva pärast äratab keegi kuningapoja üles. Kuningapoeg lööb silmad lahti, vaatab: seenekuningas ta juures.

Seenekuningas ütlema: „Tõuse ruttu üles, sõida kuningalinna. Seal räägib sinu petis kaaslane kindral, et tema on kuningapoeg ja tapnud kõik kolm koledat elukat ära. Nõuab kuningalt päästmise vaevapalgaks kuninga nooremat tütart enesele.”

Kuningapoeg kargab üles, võtab vaskvile, vilistab. Vaskhobune kohe platsis. Kuningapoeg paneb vaskriided selga, kihutab kuningalinna. Kindral parajasti kuninga juures, räägib oma suuri tegusid ja kolli tapmist. Korraga sõidab kuningapoeg vaskhobuse seljas kuninga õue peale.

Kuninga noorem tütar näeb. Hüüab rõõmuga kuningale: „Vaata, seal on õige päästja!” Kuningapoeg ei astu kuninga juurde sisse, vaid pöörab hobuse ümber, kihutab metsa tagasi. Metsas laseb vaskhobuse lahti, võtab hõbevile, istub hõbehobuse selga, kihutab hõbehobusega kuninga õue peale.

Kuninga keskmine tütar näeb. Hüüab isale: „Vaata, seal on minu õige päästja!”

Kuningapoeg pöörab hõbehobuse ümber, sõidab metsa tagasi. Metsas vilistab kuldvilet. Silmapilk kuldhobune platsis. Kuningapoeg selga ja kuninga õue peale.

Kuninga vanem tütar näeb. Hüüab isale: „Vaata, seal on minu õige päästja!” Kuningapoeg tahab metsa tagasi sõita. Kuningas aga tuleb välja ta juurde ja kutsub teda lossi päästmise palka vastu võtma.

Kuningas ütlema: „Siin on võõramaa kuninga poeg. See ütleb, tema päästnud mu tütred ära. Sind nähes tunnistavad aga mu tütred, et sina nad päästnud!”

Kuningapoeg vastu: „See, kes ennast kuningapojaks nimetab, on ainult mu kindral! ”

Kuningas imestades vastu: „Siis oled sina kuningapoeg! Tule mu juurde, ma maksan sulle su vaeva eest suure palga. Peale selle võta minu tütardest enesele naiseks see, keda tahad!”

Kuningapoeg tänab kuningat lahkuse eest. Ütleb ise: „Mul pole midagi tarvis!” Kihutab seepeale metsa tagasi, ilma et kuninga käest mingit tasu vastu võtaks. Kuningas läheb tuppa. Kihutab kindrali, kes ennast tütarde päästjaks nimetanud, sedamaid häbiga oma teed.

Kuningapoeg läheb küll metsa, aga ei jää metsa. Sõidab metsast kuldse hobuse seljas edasi, sõidab selle seenekuninga tütre juurde, kes talle kuldmuna kinkinud. Kosib selle seenekuninga tütre enesele. Jääb kuldlossi elama. Kuhu seenekuningas jäänud, ei ole teada. Kuningapoeg aga elanud kuldlossis kuldneiuga väga õnnelikku elu.