Animals

A woman went mushroom-picking in the forest. A wolf came and took the woman by her skirt and hauled her off to his den. The wolf’s pups were mostly merry and playful, but one was sad. It had a bone stuck in his throat, blocking its breathing. The wolf looked to see whether the woman herself might help the pup. But the woman wasn’t about to stick her hand in the pup’s mouth; the woman was afraid of it. The wolf pulled the woman by her skirt. Then, it pulled her down. The woman pried open the wolf pup’s mouth and there was the bone stuck in its throat. She took the bone out and put the pup back in the den, and when the pup started playing there, the wolf took the woman by her skirt and led her to the path, from which it had brought the woman to its den. The next day, the woman went into the forest again. The wolf came to her and had a big, grey sheep. It gave it to the woman.

Naine läks metsa seenele. Hunt tuli vastu ja võttis naise undrukut pidi kinni ning viis ta pesa manu. Teised pojad olid kõik rõõmsad ja mängisid, aga üks oli kurb. Temal oli luu kurgus, see takistas ta hingamist. Siis oli hunt vaadanud, et kas naine ise poega aitaks. Aga naine ei pistnud kätt, naine kartis seda. Hunt oli tõmmanud undrukut pidi naise maha. Siis tõstis poja talle käppadega sülle. Naine võttis hundipoja suu lahti ja sellel oli luu kurgus. Ta võttis luu välja ja pani poja pessa, aga siis, kui poeg hakkas pesas mängima, võttis hunt naise undrukut pidi kinni ja viis sinna tee peale, kust ta naise pesa juurde tõi. Teine päev oli naine jälle metsa tulnud. Hunt oli vastu tulnud ja tal oli suur hall lammas. Andis selle naisele.

The wolf howls to his son on the shore of Lake Pühajärv: wow, wow!

The cubs reply: bow-kow, bow-kow, bow-kow!

Ellen Liiv: Where was that child when you were reading like that, on your lap?

Bertha Ilver: No matter, on my lap or anywhere. To hush.

Hunt ulub oma poega Pühajärve kalda peal: auu, auu!

Pojad teevad vastu: kiu-kau, kiu-kau, kiu-kau!

Ellen Liiv: Kus see laps sul oli, kui sa niiviisi lugesid, süles või?

Bertha Ilver: Ükskõik, süles või ükskõik kus. Nagu vaigistuseks.

In the old days the wolf was not allowed to mention, or he would attack the herd.

Vanasti ei tohtinud hunti nimetada, sest muidu tuleb hunt karja.

On the Saint George’s Day, the halter is put on the wolf's head and taken off on Saint Michael's Day.

Jüripäeval pannakse hundile päitsed pähe ja mihklipäeval võetakse ära.

Wolf comes to herd until he sells his skin.

Hunt seni karjas käib kuni oma naha müüb.

She was an orphan girl and a suitor came to their place. She wanted him, but her mother, or actually her stepmother, mocked her and didn’t want him, of course… However, the suitor somehow succeeded to steal the desired girl.

And so the orphan started to live with this man, the suitor, and a child was born, was it a boy or a girl. The stepmother went there to the christening with her own daughter, and somehow the stepmother turned her stepdaughter into a wolf, replacing her with her own daughter. The wolf escaped. And the stepmother said: „You see, what a tramp! Look how she has left…“ [---] The child remained to be brought up by the daughter of this [evil stepmother]. But she herself left for the forest.

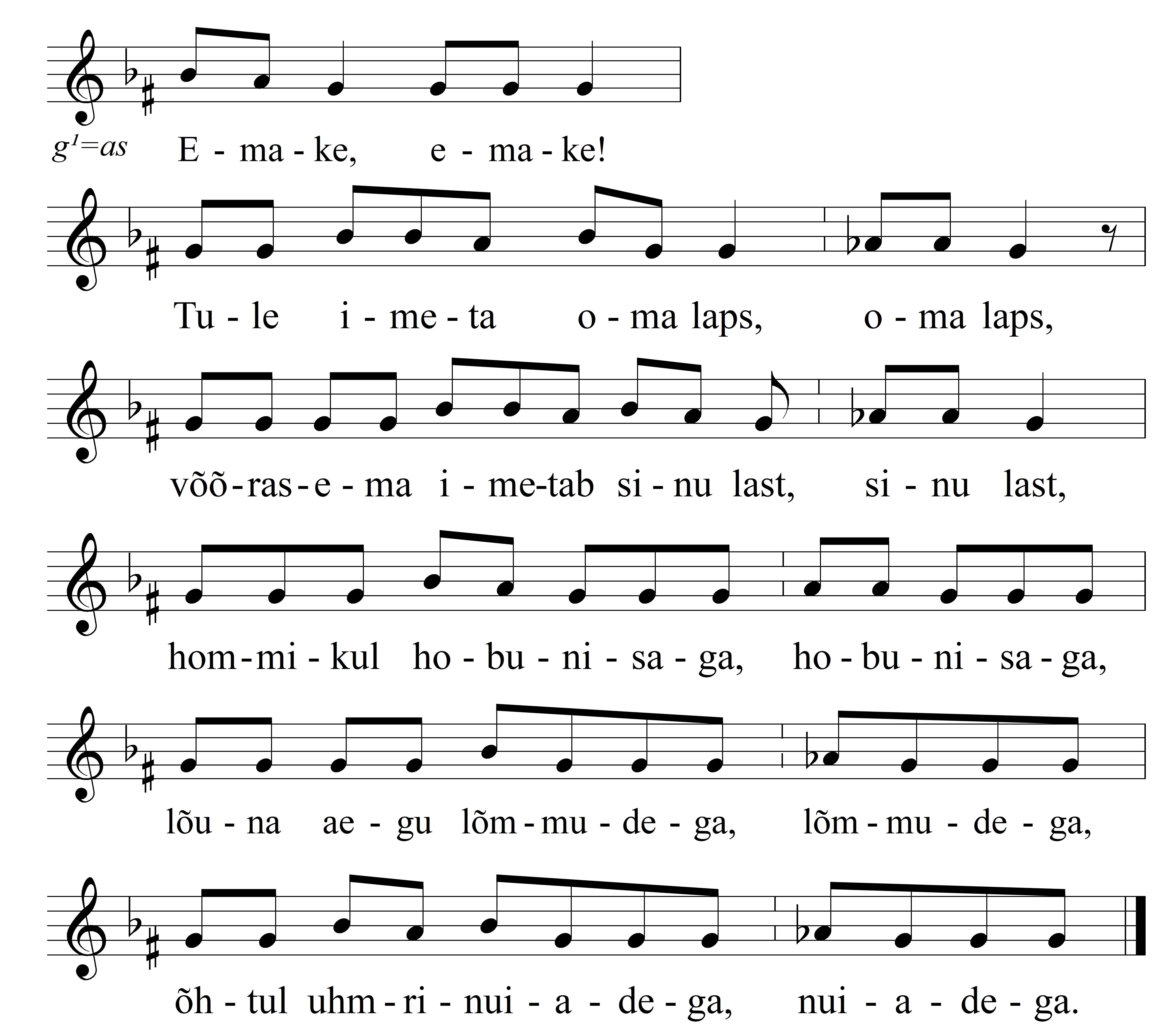

The father also had a servant, a babysitter. But the child was very restless. The daughter – and false mother – suckled the child but the breast was what it was. And the child didn’t stay long at her breast. The babysitter took the child on her lap and she understood everything; she realised that the daughter was not the real mother, and so she went to the forest and sang like this:

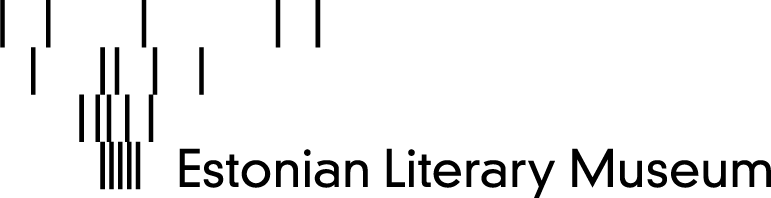

Mummy, mummy!

Come suckle your child!

The stepmother suckles your child,

By horse teats in the morning,

by mortar pestles in the evening,

by dry pine logs in the noon.1

And then the orphan – mother – came! In the old days it was said that she was wearing tar skin or wolf skin and that she threw it off. And she suckled the child and gave it back; she took her skin and went back to the forest.

But again the child didn’t stay at the breast of this devil on the second day. How could the baby accept this! So, the babysitter took the child again to the forest. But the man was also there and heard the babysitter… or he noticed that the babysitter went there with the child and sang again like this:

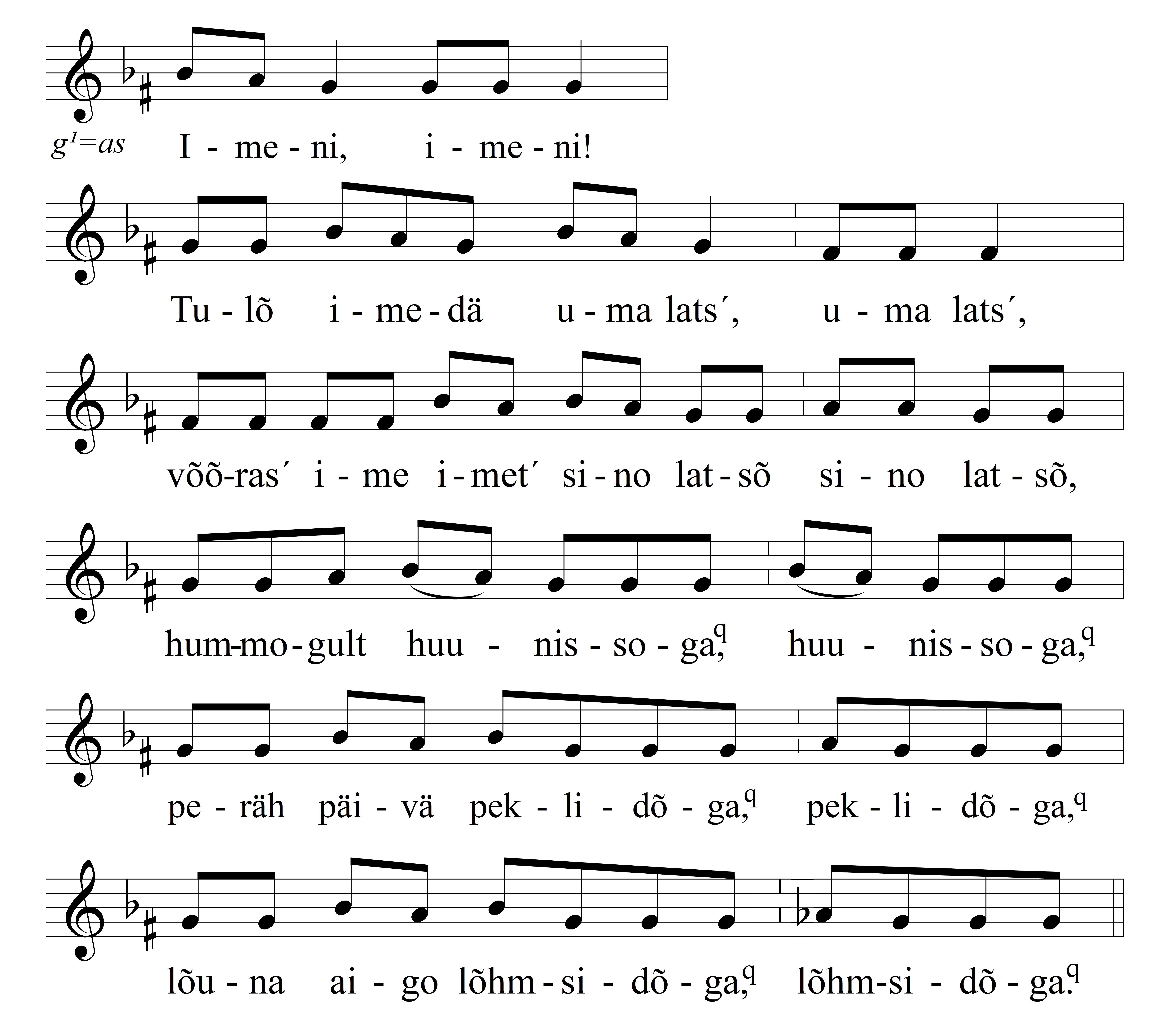

Mummy, mummy!

Come suckle your child!

The stepmother suckles your child,

By horse teats in the morning,

by dry pine logs in the noon,

by mortar pestles in the evening,

Yes, again the mother gave the child back to the babysitter. She herself pulled on the wolf skin and went back to the forest. The babysitter went home with the child.

The man then went to a sage, or witch. The latter instructed him: „Find out where she goes with the child and heat up a stone already there. See where she throws that wolf skin, and heat the stone up very, very well. When she throws off the skin and it catches fire, and she tries to escape, catch her and don’t let her go! Whatever she does don’t let her go! Finally, when she turns herself into a spindle, break it. Wrap it into a shawl and take it to the bed, and you will have your wife back.“

And this is what he did. He heated up a stone. The babysitter was singing there, and the mother came there again. He threw the skin on the stone and it caught fire. The mother wanted to escape but the man grabbed her and didn’t let her go. She turned herself into everything! The man was scared but he still didn’t let her go. Finally, she turned herself into a spindle. He broke it, wrapped it into a shawl and took it home. It became his wife again.

But the evil stepmother's daughter… I don’t remember what happened to her, or how she got killed. Maybe stones were brought to her and were placed in such a way that she died. And the man started to live with his wife again.

1There were special logs in the household, to be cut into splinters. In the comments of the other variants of the same fairy tale it has been said that the stepmother tried to make breasts out of birch bark or wood pieces.

Ta oli vaeslaps, ja sinna tuli kosilane. Tüdruk tahtis teda, aga ema, see tähendab võõrasema, siis muidugi pilkas teda ega tahtnud… Aga mees kuidagi varastas ta.

Ta hakkas selle mehega koos elama. Ja tal sündis ka laps, oli siis poisike või tütarlaps. Võõrasema läks oma tütrega sinna ristsetele. Ja võõrasema muutis ta kuidagi hundiks ja pani oma tütre sinna asemele. Ta põgenes ära, see hunt. Eks siis võõrasema ütleski et: „Näed, oli selline hulgus ja nõnda ta läkski…“ --- Lapseke jäi selle vanapagana [võõrasema] tütre kasvatada. Aga naine läks ära metsa.

Sel mehel oli võetud ka teenija, lapsehoidja. Aga lapseke oli väga püsimatu. Ta [vale ema] andis talle küll rinda mis ta andis, selline nagu see tema rind oligi. Aga laps ei püsinud rinna otsas. See hoidja võttis lapsekese sülle ja – ta teadis kõike, sai aru, et see pole õige ema – ja läks metsa äärde ja laulis seal:

Ja siis ta tuligi. Vanasti üteldi, tõrvanahk või hundinahk, mis tal seljas oli, selle viskas maha. Ja imetas lapse ära ja andis tagasi; võttis oma naha ja läks tagasi metsa.

Nõnda lapsekene teine päev jälle ei püsinud selle vanapagana rinna otsas. Kuidas ta saakski sellega leppida. Niisiis, lapsehoidja viis lapsekese jälle metsa äärde. Aga mees käis ka seal ja kuulis, et hoidja… või märkas, et hoidja läks lapsekesega sinna ja laulis nii:

Jah, [ema] andis siis lapse uuesti hoidja sülle. Ise tõmbas hundinaha selga, või soenaha, ja läks tagasi metsa. Hoidja läks lapsega koju.

Siis läks mees targa või nõia juurde. See õpetas: „Uuri järele, kuhu ta lapsega läheb, ja aja seal juba enne kivi kuumaks, uuri kuskohta ta täpselt selle naha viskab, ja aja seal kivi hästi, hästi kuumaks. Kui ta selle naha maha viskab ja nahk ära põleb ja ta tahab põgeneda, sa võta ta kinni ja ära lase enam lahti, ükspuha mis ta ka ei teeks, aga ära teda lahti lase. Aga lõpuks, kui ta moondab ennast kedervarreks, siis murra see katki, pane räti sisse ja vii voodisse, siis saad oma naise jälle tagasi.

Ja nii ta tegigi, ajas kivi kuumaks, lapsehoidja laulis seal – ja see tuli jälle. Viskas naha sinna kivi peale ja nahk läks põlema. Ta tahtis põgeneda, aga mees võttis ta kinni ega lasknud enam lahti. Ta moondas ennast kõigeks – mehel on küll hirm, aga lahti ka ei lase. Kõige lõpuks tegi ta end kedervarreks, mees murdis selle katki, pani räti sisse ja viis koju. Sellest sai uuesti naine.

Aga see vanapagana tütar, ma ei mäleta, mis temaga juhtus, kuidas ta surma sai. Kas toodi talle kive ja pandi nii, et ta sai surma. Ja mees hakkas jälle oma naisega elama.

When a wolf has many cubs, one of them is a werewolf. The werewolf attacks an animal from the back and eats it from the inside until the animal dies.

Hundil, kui temal palju poegi on, siis on tal üks poegadest libahunt. Libahunt läheb loomale tagant sisse ja sööb looma seest tühjast ja loom sureb.

[Voice.]

Anu Vissel: What was the voice?

Endel Kukk: The voice of the hare. A hare calls another hare like this in the spring, when it's mating time or running time, then he makes such a sound. Loud.

AV: Was this voice also made while herding?

AK: Sure, all the voices, of course.

[Heli.]

Anu Vissel: Mis hääl se nüüd oli siis?

Endel Kukk: Jänese hääl. Jänes kevadel niimoodi kutsub teist jänest, kui see paaritumise aeg ehk jooksuaeg on, siis ta teeb sellist häält. Kõvasti.

AV: Kas seda häält ka sai karjas tehtud siis?

AK: Sai, kõike, jah ikka.

They were habitually hunting hares. There was one old women’s chest of clothes in the corner of the field. One wall of it was removed and this is where they shot these animals. One Saturday or Thursday evening the landlord went to ambush again, but there wasn’t one hare on the freshly sprouting field. Then he thought: “This is strange. They have always been here but today there isn’t one. What the bloody hell!”

Suddenly someone knocked at the chest: rat-a-tat-tat! He said: “What are you whores doing at this chest!” Nothing.

Someone knocked another time. He thought these were girls.

It was knocked the third time. Then the man looked at what it really was. A big black man was near the chest with a firebrand in his hand. He disappeared when old Endrik threatened to shoot. Suddenly there were a zillion hares on the sprouting field. The man started to look for the biggest one, and he saw they were all calves without heads!

One young lady appeared as though she had got up from the grave. She played an instrument, trill and trill! Endrik said: “No ghost can play an instrument! It keeps trying, but no piece comes out of it. Yet I’ll play you a trick.” He shot a silver bullet. Only a blue smoke cloud was left.

Nemad olid käinud ikka jäneseid küttimas. Vana kirst, selline naiste rõivakirst, seisis neil põllunuka juures. Üks ots oli eest ära ja sealt lasksidki neid loomi. Siis, ükskord laupäeva või neljapäeva õhtul, läinud peremees jälle varitsema, aga orasepõllul polnud ühtegi jänest. Mõelnud et: „Imelik küll, igakord on neid siin olnud, aga täna polegi. Kuradi lugu!“

Järsku keegi koputanud kirstu peale: kopp-kopp-kopp! Tema öelnud: „Mis te, litsid, nüüd siia kirstu juurde tulete!“ Ei midagi.

Koputanud keegi jälle teist korda. Mees mõelnud, et need on tüdrukud.

Koputatud kolmandat korda. Siis mees vaadanud, et mis seal õieti on. Suur must mees oli kirstu kõrval, tukk käes. Kadunud ära, kui vana Endrik lasta lubanud. Ja kohe olnud orases jäneseid täis kui pihu ja põrmu. Hakanud siis vaatama, milline neist kõige suurem on. Näinud – kõik olnud hoopis ilma peata vasikad!

Üks preili ilmunud välja kui hauast, pill käes. Tõmmanud ikka pilli trill ja trill!, see preili. Tema jälle ütelnud: „Ega tont pilli mängida ei oska! Proovib küll, aga lugu välja ei saa. Aga mina õige mängin sulle ühe viguri.“ Lasknud siis hõbekuuliga. Jäänud paljalt sinine suitsupahvakas järgi.

Hare doesn't run straight and a lyar doesn't tell the truth.

Jänes ei jookse otse, valelik ei kõnele, mis tõsi.

You must not make children with hares.

If a white hare sheds at Candlemas, then it is right time to plant summer crop on Saint George's Day.

Kui valge jänes hakkab küünlapäeval karva ajama, siis alustatakse jüripäeval suvivilja külvamist.

Where is a forest, there are hares.

Kus mets, seal jänesed.

Hare says, it has a better winter apartment than the eating land in summer.

Jänes ütleb, et temal on talvine öökorter parem, kui suvine söödamaa.

A farmer went to fetch wood from the forest before Christmas. There was deep snow. His horse waded through it all the way up to its belly. He went into the forest, cut down a few trees, and started heading home with his sledge half-empty. After riding for a little while, the man sensed someone was sitting behind him. The man looks back and sees an old honey-paw bear is sitting nicely on the sledge, his back towards the man. The man reckoned: I’ll take my axe and strike once, then I’ll make a marvellous blanket from its hide – but he didn’t stir all the same, and he simply rode onward. When he was passing through the gate to his yard, the bear got off the sledge and went on its way. When the man went out in the morning, he saw a beehive standing next to his door with a lot of bear tracks around it. The man realised it had been brought by the bear – as payment for the good ride.

Enne jõulu läks talumees metsast puid tooma. Oli sügav lumi. Hobune sumas lausa kõhust saadik lume sees. Jõudis metsa, raius mõned puud ja sõitis pooltühja reega kodu poole tagasi. Said natuke maad edasi, tundis mees, et keegi istub tema selja taga. Vaatab mees tagasi, näeb: vana mesikäpp karu istub ilusasti ree peal, selg mehe poole. Mees mõtles, et võtan kirve ja äigan korra, saan toreda tekinaha – aga ei ole end liigutanud, vaid sõitis vaiksel viisil edasi. Kui ta oli õueväravast sisse sõitmas, tõusis karu reelt ja läks oma teed. Hommikul välja minnes nägi mees, et tema ukse kõrval seisis mesipuu, mille ümber nägi palju karujälgi. Nii sai peremees aru, et see on karu toodud – tasuks hea sõidu eest.

One man's mind, but nine men's strength.

In the old days, when a bear went to the oats, it was believed for sure that the bear would make the oats grow and prosper, or that a bear in the oats blesses the grain and brings profit.

Moose calf, moose bull, he-goat.

Põdravasikas, põdrapull, sokk.

Anu Korb: [How] were they lured to you?

Mihkel Prinken: Well, that's right, every animal comes and it happens at a certain time, but the moose is such an animal that you can call him to you most of the time. He comes to you both in winter and summer. The only keeping him away is the wind. It depends on where you are and where the animal is. If he happens to come against the wind, he will not come to you. But he still wants to meet the other. And mostly is possible to see him with the means of the voice.

Of course, it is during the evening meal, when the animal comes to eat. Then he is eating, and he downright listens, he talks. Is there another nearby? At times he makes calls, and then a bit anxiously listens if there is anybody somewhere. In case you can hear him - aha, there he is shouting! – answer him. They are like chatting

The other there goes: "Aah!"

And when you hear that he's "Aa"ing there, you answer here: "Oo!"

After a little while, he replies again: "Aah!"

After a while, you repeat again: "Oo!"

Then he starts coming. Then he comes.

"Aa!" – "Oo!" - "Aa!" – "Oo!"

And then some time will pass. Now that he already thinks he can get close to you, he makes one more noise and then listens to where are you now. He can tell right away by your voice how far you can be from him. He immediately measures the land with his ears.

But if you move there and spread your smell, you can't see him, he won't come.

But he has come, I have invited him to very close. If he happens to come well, he comes up to 4-5 meters away, comes to you, if he doesn't glimpse you. You have to hide so that he doesn't see. If he doesn't smell. If he can smell you, he won't come.

And so are other wild animals. If you sound right, you can always call them. Come, come! He, damned, does not come.

Mart Jallai: Let's make that calling sound!

MP: That sound was like what I was doing right now. That's the call. And the young animal has, when they are separated again, let's say a moose cow and a calf, then --- the calf whistles. It [the cow?] has it's special whistle, deeper than the other one. It sounds about like this:

[Whistling,]

About like this, such a whistle.

But the cow whistles, the cow has a deeper whistle. But they daw themselves together with a whistle. They are sometimes apart for certain periods of time. And the calf is not always with her. Then the calf is already bigger. It's parent is already getting it used to going alone and then again meeting in the forest, because... Sometimes it happens that they are very far apart, if either of them... let's say, for example, runs into dogs. It goes away, and then it is running for a certain amount of time, but it still comes back to this area to search the other. Then they whistle to each other. A calf and a cow always whistle when they want to get together. So they don't make that much louder noise, they still whistle when they want to get together.

But if you, a human, don't know anything about this whistle, you won't notice, so you can go without knowing anything about this whistle. You don't understand.

Anu Korb: [Kuidas] enda juurde neid peibutati?

Mihkel Prinken: Noh, see on niisukene asi et, egä loom tuleb juure ja see on teatud ajal, aga põdra on niisukene loom, et teda võib suurem jägu juure kutsuda alati. Tema kui talvel ja kui suvel, ta tuleb juure. Ainukene on see, mis ära oiab – tuul. Oleneb nii, et kuskohas sa oled ja kus see loom on. Kui juhtub, et ta vasta tuult tuleb, siis ta sulle juure ei tule. Aga kokku ta tahab ikkagi teisega saada. Ja näha võib teda suurem jagu alati saada hääle järgi.

No muidugi see on õhta süömise ajal, kui luom tuleb süöma. Siis tema süöb, ta kuulab kohe, tema ajab juttu. Kas on teist seal lähedal olemas? Tiatud aja tagant tieb äält, tema väiksel äristusel kuulab, kas on kuskil midagi. Juhul, kui sa ta ära kuuled – ahah, seal ta karjub! – vasta temale. Neil on nagu jutua'amine.

Teine tieb seal, tieb: "Aa!"

Ja kui sa kuuled, et tema seal aatab, sa tie siin vasta: "Oo!"

Ta tieb jälle vasta vähe a'a pärast: "Aa!"

Sa korda jälle vähe a'a pärast: "Oo!"

Siis akkab tema tulema. Siis ta tuleb.

"Aa!" – "Oo!" – "Aa!" – "Oo!"

Ja siis on ta teatud jagu aeg. Nüüd, kus ta juba arvab, et ta saab sinna ligi kohta, siis tieb korra viel äält ja siis kuulab – kus ta nüüd on? Märkab ära kohe selle ääle järele, kui kaugel sa olla võid, tähendab temast. Tema mõõdab maa otsekohe oma kõrvadega ära.

Aga kui sa seal liigud ja lõhna a'ad, siis sa teda näha ei saa, siis ta ei tule.

A ta on tuld, ma ole teda kutsunud päris juure. Kui ta trehvab easti tulema, siis tuleb kuni 4-5 mietri piale, tuleb sulle juure, kui ta sind ei silma. Sa pead niimoodi varjama, et ta ei näe. Kui ta lõhna ei tunne. Kui lõhna tunneb, siis ei tule.

Ja nii on metsloomad kõik. Ja ääldus on sul kääs, siis võid alati juure kutsu. Tule, tule! Teda, kurat, ei tule.

Mart Jallai: Teeme seda kutsumise äält!

MP: See ääl oli nii, nagu ma praegu tegin just. Niisamasugune ääl ta on. Ja noorel loomal on, kui nad jälle lahus on, ütleme lehm ja vasikas on, siis --- vasikas vilistab. Temal on oma vile, aga vile on jämedam kui teisel, umbes sarnane vile on:

[Vilistamine,]

Umbes sarnane, niisukene vile.

Aga lehm vilistab, lehma vile on jämedam. A nemad vilega võtavad endid kokku. Nad on teinekord teatud aegu lahus. Ja see vasikas ei ole alati tal juures. Siis on juba vasikas suurem. Tema vana nagu arjutab teda üksinda juba käima ja siis kokku saama metsas, sest et... Teinekord on niisukene juhus, on palju vahet, aga nüüd kumbki... kas ütleme, kas koerte ette sattub või. Läheb minema, aga siis ta küll jookseb oma teatud aja ära, aga ta tuleb ikka siia sellesse ümbrusesse taga otsima jälle. Siis vilega vilistavad. Vasikas ja lehm on alati vilega, tahavad kokku saada. Nii et nad palju niisukest valjumat äält ei tie, ikka vile on, kellega nad kokku saavad.

A kui sa seda vilest ju, inimene, ei tia, ei märka, sis sa võid käia, sa ei tia üldse sest vilest mitte midagi. Sa ei taipa.

Once upon a time, there was an old woman who had three geese. She went to look for a gooseherd. On her way, she met a rabbit. The rabbit said: “Hello, hello, village woman, where are you going?” She said: “I’m going to another village to look for a gooseherd.” The rabbit said: “Take me!” The old woman said: “How do you sing?” The rabbit began to sing: “Whoah, whoah whoah, whoah whoah.” The old woman said: “I can’t take you; you will scare my little geese away.”

She walked on and met a wolf. The wolf said: “Hello, hello, village woman, where are you going?” The old woman said: “I’m going to this other village to look for a gooseherd.” The wolf said: “Take me!” The old woman asked: “How do you sing?” The wolf said: “I sing like this: “Howl howl howl howl.” The old woman said: “Phoo, you will not be fit as a gooseherd, you will scare my geese off.”

The old woman continued on her way and met a fox. The fox said: “Hello, hello, village woman, where are you going?” The old woman answered: “I’m going to another village to look for a gooseherd.” – “Take me,” said the fox. “How do you sing?”

The fox sang:

Diddlee diddloo,

the herd is eating on the shore,

I am playing on the hill.

The old woman said: “I’ll take you.” And she took the fox home to be the gooseherd.

Then the old woman drove the geese into the forest and put the fox on guard. While herding, the fox began to sing:

Diddlee diddloo,

the herd is eating on the shore,

I am playing on the hill.

After that, he added these words, “the goose’s throat - chomp,” and he snapped a goose and ate it. He then went home with two geese following him. The old woman said: “My son, where is the other goose? Only two geese are coming home. Where is the third one?” The fox said: “Oh, grandma, he stayed behind the gate to eat on the green grass.” Then the fox took a broom and started sweeping the room. In the middle of sweeping, he said “he he he!”. The old woman asked: “My son, what came to your mind?” The fox said: “I was invited to the village to baptize children. The old woman said: “Wait, my son, I’ll bake a scone for you to take with you; you can’t go with your hands bare.” The old woman baked a scone. But instead, the fox took the scone and sneaked into the attic. The old woman had honey in the attic (some say butter, some say honey, some say fat). And there he ate honey with the warm scone and then came down. The old woman asked: “My son, what name did they give to the child?” “Beginning,” the fox said.

Then the next day, the geese were driven into the forest again. That day again, the fox ate a goose. In the evening, the fox came home with only one goose. The old woman asked: “My son, where are the other two geese?” The fox said: “The other one also stayed eating on the green grass.” Then the fox said to the old woman: “I was invited to visit the village again today to baptize children.” The old woman said: “Go, go!” The fox instead went up into the attic and ate half the honey. He then came down from the attic. The old woman asked again: “My son, what name did they give to the child?” – “Halfway Through,” said the fox to the old woman.

Then the only goose was driven into the forest again. In the evening, the fox comes home alone. The old woman asked again: “My son, where are all the geese so that you come home alone?” – “I left them all on the green grass behind the gate.” Then he said: “Grandma, I’m going to a baptism today again.” The old woman said: “Then go, go today too if you were invited.”

The fox ate the rest of the honey, came down from the attic,1 and said to the old woman: “Grandma, I’m sick.” The old woman said: “I will heat the sauna. Go to the sauna, and you will get better.” Then the old lady heated the sauna, took the gooseherd to the sauna, put him onto the bench, and said: “My son, let me whisk you.” The old woman whisked and washed and looked and saw something coming out of the gooseherd’s butt. And she saw a goose feather was coming out of his butt. The old woman realized that the gooseherd had eaten the geese. The fox also realized that the grandmother knew that he had eaten the geese. The fox slipped off the bench and out of the sauna, saying: “Lick my butt, lick my butt, granny! I ate your honey, I ate your geese, and I ate your scones.” And off he went to the forest. End of story.

1 In several versions of the story, the grandmother also asks the name of the third child, that is "Ending."

Elas eideke, tal oli kolm hane. Läks hanekarjust otsima. Talle tuli vastu jänes. Too ütles: „Tere, tere, külanaine, kuhu sa lähed?“ Tema ütles: „Ma lähen teise külla hanekarjust otsima.“ Jänes ütles: „Võta mind!“ Vanaemake ütles: „Kuidas sa laulad?“ Jänes hakkas laulma, tegi nii: „Huu, huhuhuu, huhuhuu“. Vanaemake ütles: „Ei saa ma sind võtta, sa hirmutad mu hanekesed ära.“

Siis tuli vanaemakesele vastu hunt. Hunt ütles: „Tere, tere, külanaine, kuhu sa lähed?“ Vanaema ütles. „Lähen sinna teise külla hanekarjust otsima.“ Hunt ütles: „Võta mind!“ Vanaemake küsis: „Kuidas sa laulad?“ Hunt ütles: „Ma laulan: „Au, au, au, au.“ Vanaemake ütles: „Võeh, sinust karjust ei saa, sa ehmatad mu hanekesed ära.“ No siis tuli vanaemakesele rebane vastu. Rebane ütles: „Tere, tere, külanaine, kuhu sa lähed?“ Vanaemake vastas: „Lähen teise külla hanekarjust otsima.“ – „Aga võta mind,“ ütles rebane. „Kuidas sa laulad?“ Rebane laulis:

Kireluu, kareluu,

kari sööb kaldal,

ise mängin mäe peal.

Vanaemake ütles: „Sinu küll võtan.“ Ja viiski rebase koju. Siis ajas vanaemake haned metsa ja pani rebase valvama. Rebane hakkas karja juures laulma:

Kireluu, kareluu,

kari sööb kaldal,

ise mängin mäe peal.

Pärast lisas kaks sõna juurde: „hane kõri lõmpsti“ ja krapsaski hane kinni ning sõi ära. Läks koju, kaks hanekest järel. Vanaemake ütles: „Pojake, kus üks hani on? Ainult kaks hanekest tulevad koju. Kus kolmas on?“ Rebane ütles: „Oi, vanaemake, jäi värava taha halja heinakese peale sööma.“ Siis võttis rebane luua ja hakkas tuba pühkima. Keset pühkimist tegi „hii!“. Eideke küsis: „Poeg, mis sul meelde tuli?“ Rebane ütles: „Mind kutsuti külla lapsi ristima. Vanaemake ütles: „Oota, pojake, ma küpsetan sulle karaski kaasa, kuidas sa paljaste kätega lähed.“ Vanaema küpsetaski karaski. Aga rebane läks pööningule. Vanaemal oli pööningul mett (mõni ütleb võid, mõni mett, mõni rasva). Ja seal ta sõi mett sooja karaskiga ning tuli pärast alla. Vanaemake küsis: „Pojake, mis lapsele nimeks sai?“ Rebane ütles, et Alang.

Siis aeti haned jälle metsa. Rebane sõi ka sel päeval ühe hane ära. Õhtul tuli rebane koju ainult ühe hanekesega. Vanaemake küsis: „Poeg, kus sul kaks hane on jäänud?“ Rebane ütles: „Teine jäi ka halja heinakese peale sööma.“ Siis ütles rebane vanaemale: „Mind kutsuti täna jälle külla lapsi ristima.“ Vanaema ütles: „Mine, no mine!“ Rebane läks ja sõi pool mett ära. Tuli pööningult alla. Vanaema küsis jälle: „Pojake, mis lapsele nimeks sai?“ – „Pooleng,“ ütles rebane vanaemale. Siis aeti too ainus hanekene jälle metsa. Õhtul tuleb rebane üksi koju. Vanaema küsis jälle: „Poeg, kuhu hanekesed on jäänud, et üksinda koju tuled?“ – „Kõik jätsin värava taha halja heinakese peale.“ Siis ütles: „Vanaema, ma lähen täna ka veel ristsetele.“ Vanaema ütles: „Mine, no mine siis täna ka, kui kutsuti.“

Rebane sõi ülejäänud mee ka ära, tuli pööningult alla1, ütles vanaemale: „Vanaema, ma olen haige.“ Vanaema ütles: „Ma kütan sauna. Käi saunas, siis hakkab parem.“ Siis küttis vanaema sauna, viis karjuse sauna, pani lavale ja ütles: „Pojakene, ma vihtlen ka sind.“ Vanaemake vihtles ja pesi ja vaatab, et ei tea, mis karjusel tagumikust välja tuleb. Ja vaatab, et hanesulg tuleb tagumikust välja. Vanaema sai aru, et karjus on haned ära söönud. Rebane sai ka aru, et vanaema teab, et ta on haned ära söönud. Rebane lipsti lavalt maha ja saunast välja, ise ütles: „Laku perset, laku perset, vanaemake! Mina sõin su meekese, sõin su hanekesed, sõin su karaskid.“ Ja läks metsa. Juttki otsas.

1 Mitmes jutuvariandis küsib vanaemake ka kolmanda lapse nime, see on "Lõpõng."

Fox will steal no chickens from near home.

Ega rebane kodu lähedalt kanu varasta.

The one who seeks a hedgehog, will find a pig.

Kes siili otsib, see sea leiab.

Hedgehog gets bear out of the nest.

Siil ajab karu pesast välja.

A long, long time ago, a fox found some fish remains on the lake by the fishing hole that a fisherman had just left and started eating them. A wolf also happened to come along. His tail was ringed like that of all wolves in old times. He started talking to the fox:

“Cousin, where did you get those fish?”

The fox replied: “I caught them from the hole with my tail. If you also want to catch them, stick your tail in the hole and keep it in the water for a few hours. Then there will be so many fish hooked onto it that you will have a hard time dragging them out.”

“I see! I do want to catch them. So, I will stick my tail into the hole,” said the wolf and did what he had promised.

After a while, he moved his tail. It was difficult because the hole was already covered with quite a thick layer of ice. He wanted to pull out his tail, but the fox stopped him and said: “Don’t do it that soon! Wait twice as long!”

So, the wolf waited some more. When the fox thought it had been long enough, he said:

“Now you can pull! Now there should be a good catch!”

The wolf pulled, but the tail did not come out. The fox laughed and said that the catch was very big and that the wolf should pull harder. The wolf pulled again as hard as he could, but the tail did not come out. The fox said again:

“Dear cousin, pull again fast with all your might! If you rest for a long time, more fish will hook on to the tail, and you will never be able to get your tail back from them; you will have to leave it there if you don’t want to croak. Goodspeed for now! I can’t help you, and I have urgent things to do.”

The fox took leave, laughing his head off. The wolf, the poor man, tried for the third time and managed to drag his tail out of the ice, but it was so damaged that he could no longer pull it into a ring. Since then, the wolf’s tail has been limp.

Ennemuiste leidis rebane järve peal kalaaugu äärest, kust kalamehed parajaste ära olivad läinud, natukene kalariismeid ja hakkas neid sööma. Hunt juhtus ka sinna. Saba teisel rõngas, nagu ennemuiste ikka huntidel olnud. Ta hakkas rebasega rääkima:

„Sugulane, kust sa need kalad said?“

Rebane vastu: „Sabaga püüdsin august. Soovid sa ka neid saada, siis pista saba seie auku ja hoia teda mõni tund vee sees. Siis on tal niipalju kalu külles, et sul neid üsna välja tiruda1 saab.“

„Soo! Ma tahan neid küll saada. Pistan siis peale saba auku,“ ütles hunt ja tegi ka, kudas lubas.

Tüki aja pärast liigutas ta saba. See oli raske, sest kaunis paks jääkord oli juba augul peal. Ta tahtis saba juba välja tõmmata, aga rebane keelis ära ja ütles:

„Ei maksa veel nii ruttu! Oota kaks kord niipalju aega veel!“

Hunt ootas ka veel. Kui rebane juba paraja aja arvas olevat, ütles ta:

„Nüüd võib juba tõmmata! Selle aja kohta peaks ikka loomust ka olema!“

Hunt tõmbas ka, aga saba ei tulnud välja. Rebane naeris, et loomus olla väga suur ja tarvitada tublit tõmbamist. Hunt tõmbas uueste kõigest jõust, aga ei tulnud.

Rebane jälle: „Aus sugulane, kärista ruttu jälle kõigest jõust! Kui sa kaua aega puhkad, kogub ikka enam kalu saba külge ja sa ei saa ilmaski teda enam nende käest kätte, vaid pead ta seie paika jätma, kui ise kärvata ei taha. Jumalaga seekord! Mina sind aidata ei saa ja mul on pakiline aeg.“

Rebane läks nagu koer, naerdes kus see ja teine. Hunt, vaene mees, tirus kolmandal korral küll saba jää seest välja, aga see sai niiväärt2 vigaseks, et teda enam ei suutnud ülesse rõngasse tõmmata. Sellest ajast saadik on hundi saba sorgu.

1 tirida; 2 niivõrd

Once, the fox wandered into the forest together with the wolf and found a dung beetle on the ground at the last year's campfire site. The fox told the wolf to taste it to see if it was good. The wolf tasted it and praised it, saying it was crispy. He also allowed the fox to eat it, but the fox said I am generously leaving it to you. So the wolf happily ate the beetle.

that, they wandered some more through the forest and came to a haystack. There they found the haymakers' lunch on the ground. The fox said:

"Now it's my turn to taste."

He started to taste it, but he spat out the first bite and said:

"Ow bro! Look, it is really bad and bitter! It is no good!"

The wolf said: "Let me have a little bit too."

But the fox forbade that, saying, that brother, you don't need to even have to spoil your mouth with it. It is bad and terrible and horrible. But look, I'm starving to death, and I am still barely able to eat it. And the fox ate everything by himself, and the wolf could not get a single mouthful.

So they wandered on again and came to a threshing barn. There, the grain was hung up and drying there. The fox said:

"Bro, it is us that should thresh this grain. Then we would have stocks for winter, just like everybody else."

The wolf agreed, and they started working. The fox went up to the threshing logs and started throwing down the sheaves from there. He through the entire threshing down, but he himself stayed up. He was just sitting on top of the threshing logs and watched the world threshing as if there was no tomorrow.

But look, finally, the wolf got tired and shouted to the fox: "Come on, pal! How long do I have to thresh here alone! What the hell are you sitting up there on the logs and not working? But look, I can't do it alone anymore!"

The fox on the threshing logs does not budge, and he says to the wolf: "Well, look, dear brother, I'm saving your life here. Look, bro, I can't even move from here. I'm holding on to the end of the log here, otherwise it would fall on your head and kill you to death."

The wolf heard him, got really scared, and said: "Alright. So stay on the logs and hold them, I'll thresh the grains by myself. If I survive."

That's how Susi threshed all the grain all by himself. He looked like he had fallen into the water, he was dripping. But the fox perched on the threshing logs. After all the grain was together, the wolf called out to the fox:

"Come now down! Let the log go, the grain is together, let's start cleaning!"

Then the two of them winnowed the thresh, got all the grains clean. They started dividing them up. The fox said:

"Bro, you did more work threshing than I did holding the log. You should get a bigger pile, and I'll keep the smaller one."

Susi was satisfied with that, took the large pile of straw and chaff for himself, and left a small pile of grain for the fox.

The fox baked himself a loaf of grain flour bread, whereas the wolf's straw bread could not hold together.

Once, the wolf asked the fox: "Brother, why is your bread so hard?"

The fox explained: "Well, isn't it only fair, brother? Look, you did a lot of work threshing, and your bread is nice and soft. But for me, eating my bread is more work than threshing. I can hardly even take of a bite of the bread."

Ükskord hulkus rebane soega metsa pidi ja leidsid mullutselt tuleasemelt sitasitika maast. Rebane käskis soel toda maitsta, et kas on ka hea. Susi maitses kah ja kiitis, et krõbe on küll. Lubas rebasel ka süüa, aga rebane ütles, et ma jätan ta hea mehe poolest sulle. Susi sõi ka hüval meelel sitika ära.

Pärast seda hulkusid nad metsa pidi edasi ja jõudsid ühe heinasao manu. Seal oli heinaliste söök maas. Rebane ütles:

"Nüüd on minu kord maitsta."

Hakkas ka maitsema, aga sülgas esimese suutäie maha ja ütles:

"Oih, veli! Vaata paha mõru on! See ei kõlba kuhugi!"

Susi ütles: "Las ma ka maitsen raasukese."

Aga rebane keelas ära, et sellega, veli, ei maksa sul oma suudki ära solkida. Too om paha ja halv. Aga vaata, mul on ju nälg surmaks ja ma ikka söön hädaga sellesamagi ära. Ja rebane sõi üksinda kõik ära ja susi ei saanud ühtki lõuatäit lõpsatada.

Nii hulkusid nad siis jälle edasi ja jõudsid ühe rehe manu. Sinna olid ahted üles pandud. Rebane ütles:

"Veli, see vili oleks meil endile vaja maha peksta. Siis saaksime endile ka talvevara, nagu kogu rahval om."

Susi oli ka tollega rahul ja hakkasid tööle. Rebane läks üles parsile ja hakkas sealt viljavihke maha loopima. Ajas kogu rehe alla, aga ise jäi üles. Istus aga muudkui parre otsa peal ja kaes, kuidas susi all reht peksis, nii et tolmas.

Aga vaata, lõpuks väsis susi ka ära ja hõikas rebasele: "Tohho tigevaim! Kauas ma üksinda peksan! Mida imet sa seal parsil konutad, ei tule töö poolegi! Aga vaat ma ka enam ei jõua!"

Rebane parsil ei kõssagi, ütles ainult soele: "No vaata, kulla veli, ma hoian siin su elu. No näe, veli, ma ei või ennast siit paigast liigutadagi. Ma pean siin parre otsa kinni, muidu kukuks pars sulle pähe ja tapaks su ära koolnuks."

Susi kuulis toda, heitus kangesti ja ütles: "Olgu peale. Ole sa siis parsil ja pea part kinni, küll ma üksinda ka rehe ära peksan. Kui aga ellu jään."

Nii peksis susi rehe üksinda ära. Oli teine lige nagu vette kukkunud, tilkus lausa. Aga rebane muudkui kõhutas parre otsas. Pääle selle, kui vili sai kokku aetud, hõikas susi rebasele:

"Tule nüüd ära maha! Lase pääle pars vallale, rehi on ju koos, hakkame puhastama!"

Tuulasid siis kahekesi rehe ära, said kõik terad puhtaks. Hakkasid jagama. Rebane ütles:

"Veli, sa nägid ikka reht pekstes enam vaeva, kui ma part kinni pidades. Sa peaksid ikka suurema hunniku saama, aga mulle jäägu siis väiksem."

Susi oli sellega ka rahul, võttis enesele suure õle- ja aganahunniku, aga rebasele jättis väikese terahunniku.

Rebane küpsetas enesele terajahust leiva nagu sõira, aga soel ei püsinud õlgine leib kuidagi koos.

Ükskord küsis susi rebase käest: "Veli, mispärast sinu leib nii kõva on?"

Rebane seletas: "No kuidas veel õigem oleks, veli? Vaat sina nägid pekstes enam vaeva ja sinu leib on hea pehmekene süüa. Aga mina näen oma leiva man enam vaeva kui reht pekstes. Kuidagi ei jaksa leivasuutäit hammustada."

In old days a wolf and bear said: "Man walking in forest should whistle, then we will not get at him."

In ancient times, a mouse lived together with a sparrow, and they had no other friends. They went out to look for food, brought it home, and split everything in half. Once, they found grains of wheat and began splitting them. The sparrow said: "If we split them, neither of us will have enough. Let us better sow the wheat, and then in the fall, we'll get ten times more if it grows well." The mouse agreed with that.

The mouse plowed the ground, and the sparrow harrowed behind him. They sowed wheat, and the wheat grew big. In the fall, when the wheat began to ripen, the sparrow picked all the grains from inside the heads of grain, leaving only one grain inside each head of grain. When the wheat was ready, they harvested it and put it in a pile. They started dividing the grains, and the mouse saw that there was only one grain in each head and said to the sparrow: "You've eaten the grains!"

The sparrow said: "You've carried them to the den! I wouldn't have been able to eat that much!" The sparrow took the last grain of wheat for himself as well.

The mouse said: "Bite it in half!"

The sparrow said: "I will not!"

The mouse said: "If you don't bite it, I'll go and complain to the king."

The sparrow said: "Go, I won't stop you!" And both went their separate ways.

The mouse went to the bear, his king, to complain that the sparrow had eaten all the grains of wheat. The sparrow again went to the eagle, his king, and explained what had happened. The eagle said: "If they come to ask you, don't give them anything!" The bear and the mouse came to ask the sparrow: "Are you going to bite the grain in half or not?" The sparrow said: "I will not!"

Then the bear got angry, went to the eagle, and said: "Can't you talk sense to the sparrow! He ate all the wheat grains and left nothing for the mouse!"

The eagle said: "I didn't stand there watching, I have no idea who ate the grains!" The bear got really angry that the eagle was contradicting him and pulled all the skin off the eagle with his claws. The eagle remained there as if it had been skinned.

A man was hunting and saw an eagle sitting on a rock and wanted to kill him. The eagle started begging: "Don't kill me! I will be no good for you! Take me home and feed me a fattened ox every day! Then I will get well and help you." The man did not kill the eagle and took him home, giving him a fattened ox every day. He fed all the fattened eggs to the eagle.

His wife said then: "Take him to the forest and kill him! You fed him all the fattened oxen, but he didn't get well!"

The man took the eagle by his feet, took him to the forest, and wanted to kill him. Then the eagle starts begging again: "Don't kill me! Take me home and feed me for a week! Give me at least one goose every day! Then I will be healed."

The man took the eagle home again and gave him a fat goose every day. He fed all the geese to him, but the eagle did not recover. His wife said then: "Now take him to the forest and kill him! You have already fed him all the oxen and geese, but he still hasn't gotten well." The man took the eagle to the forest again and wanted to kill him. The eagle began to beg the man again: "Don't kill me yet! Take me home and give me at least one chicken every day. Then I will be healed." The man thought: "I have a lot of chickens; I'll take him home this time again. Come what may!"

He took him home and gave him one chicken every day. He fed all the chickens to him, but the eagle still

didn't get well. He took him home and gave him one chicken every day. He fed all the chickens to him, but the eagle still didn't get well. Then the wife said again: "Come on, take this bloody eagle to the forest already and kill him! He ate all the oxen, geese, and chickens." The man took the eagle to the forest and said: "Now I will kill you for sure!" The eagle said: "Dear man, let me live just this once! Take me home and give me at least one egg a day; maybe I'll get better."

The man felt sorry for the eagle and took him home and gave him one egg every day. The man's wife was really upset, but the man ignored her. He fed all the eggs to the eagle. The eagle was healed, and the skin was back on as before.

The eagle said to the man: "Come sit on my back, I'll take you to see the world!"

The man said: "I dare not sit down, you will drop me or take me somewhere very far so that I cannot come back."

The eagle said: "Don't be afraid of anything, I won't drop you! And if I take you far, I will also bring you back." The man sat on the eagle's back, and the eagle took off.

The woman said after them: "Look what a fool, going to the sky with his eagle. That's why he kept feeding him all the time. He fed him all the oxen and geese, chickens and eggs, and I was left with nothing."

The eagle said: "Dear woman, he will bring back many more! Wait and give him some time!"

The eagle flew over the sea and descended. The man shouted: "Don't go down, it's very scary!" The eagle said: "I was just as scared when you took me to the forest."

The eagle flew across the sea and further from there until he reached home. Both went to the house where the eagle lived with his family. Everyone was happy that the king had come home and asked: "Where have you been for so long? We thought you were dead." The eagle said: "Otherwise, I would have died if this man had not saved my life." The man was given food and drink, whatever he wanted.

Then the eagle gave the man a golden egg and said: "This is a lucky egg, I will give it to you." This egg was wrapped in a rag, and the eagle said: "Don't look or open it until you get back to your land! When you open this egg, a big city will grow there." The eagle told the man to sit on his back and started to bring him back. He brought the man across the sea and let him get off and said: "Go home now; I'll go back!" He said goodbye to the man and flew home.

The man came and held the egg in his hand all the time and thought: "I should see what it's like. Look, I fed and fed the eagle, and he didn't die. I even got a golden egg, but I should check; maybe it's not golden, maybe it's iron or pewter."

The man took the egg, unwrapped it from the rag, and looked - a golden egg, very beautiful, shining and all. He looked up and saw: there was a city around him. But he was not yet on his land. And then the man suddenly remembered that the eagle had only allowed to look at it on his own land and that if he did, a big city would emerge around him.

The man wonders what will happen now. And he sees: the eagle flies to him again and asks: "What are you thinking about?" The man said: "I'm thinking about what will happen now - I looked at the egg, and a big city appeared. But this is not my land yet." The eagle said: "Well, you didn't listen to me this time, even though I told you not to look at the egg. I came to help you." The eagle said: "Give the egg here!" The man gave the egg to the eagle, and the eagle wrapped the egg in the rag again. Suddenly the city disappeared, and the eagle gave the egg to the man again. The eagle said: "When you get to your land, unwrap it. Then a big city will appear, and you will be its king." The people saw that there was a city and then disappeared again and wondered what was going on.

The man then went to his land and unwrapped the egg, and a big city appeared, and in the middle of the city, there was a beautiful castle, and he himself was there with his wife and children, all wearing fancy clothes. His wife asked: "Where did it come from?" The man said: "The eagle did this because we fed him all the oxen, geese, chickens, and eggs." The man took out the golden egg from his pocket and showed it to his wife: "Look, this made us the city and made us its rulers." The wife said: "Bring it here, I'll have a look!" The man handed the egg to his wife, and the city disappeared. They saw that they were in the same old house where they had lived before. The man said: "That is what happens when you look at it! Give it back to me!" The wife gave the egg to the man, and the same city appeared again. The man understood that he could not put the egg anywhere else or give it to someone else but only keep it in his own hand.

The man began to live in the city with his wife, and the man was a king, the woman a lady. The man kept the egg in his pocket all the time. The woman could not hold back and told her acquaintances: "My husband has such an egg." One of the king's subjects bore a grudge against the king and wanted to steal the egg, always looking for a way to steal it. Once, the king went to the lake and went bathing. That man went secretly there and took the egg from his pocket. Suddenly the city disappeared, and they ended up living in the same house where they had lived before. Then the man realized that someone had taken the egg. After that, the wife got cross: "Why didn't you take care!"

The man went into the forest to cut down an ovenful of wood. He went along the road and thought: "I wonder where my friend the eagle is? I wish he would come to help and tell me where the egg was." Suddenly the eagle flew up to him and asked: "What's your problem?" The man explained: "I went bathing, and someone took my egg, and now I'm poor again in my little hut." The eagle said: "I want to help you again for helping me and listening to me. The egg is in the hands of one of your minions, he bore a grudge against you, and he stole it. I'll give you a gold twig, go beat him with it, and he'll give you the egg back again." The man took the twig and went to beat the one who had taken his egg. Then this man began to beg, "Don't beat me anymore!" and returned the egg. As soon as he picked up the egg, a large city appeared again, as it was before.

Now he didn't dare to bathe anywhere or leave the egg anywhere. They lived in the city until they died, and the man was the king. When the king died, the city disappeared, and so did the egg. No one knows where it went. The woman ended up living in her hut again for telling the man to take the eagle to the forest and kill it. As long as he lived, he saw a good life. The eagle wanted to take revenge on the bear for skinning him. But such a time never came. From then on, the mouse was no longer friends with the sparrow.

Ennevanasti elas hiir varblasega koos, teisi sõpru neil ei olnud. Käisid süüa otsimas, tõid koju ja jagasid kõik pooleks. Ükskord leidsid nad nisuteri ja hakkasid neid jagama. Varblane ütles: „Mis meile sellest vähesest saab, kui me pooleks jagame. Parem külvame nisu maha, siis sügisel saab kümne võrra rohkem, kui hästi kasvab.“ Hiir oli sellega rahul.

Hiir kündis maa ära ja varblane taga äestas. Külvasid nisu maha ja nisu kasvas suureks. Sügisel, kui nisu hakkas valmis saama, nokitses varblane viljapeade seest kõik terad ära, jättis iga viljapea sisse ainult ühe tera. Kui nisu sai valmis, siis lõikasid vilja ja panid hunnikusse. Hakkasid teri jagama ja hiir vaatab, et iga viljapea sees on kõigest üks tera, ning ütles varblasele: „Sa oled terad ära söönud!“

Varblane ütles: „Sa oled urgu kandnud! Ma ei oleks jõudnud nii palju ära süüa!“ Varblane võttis viimase nisutera ka endale.

Hiir ütles: „Hammusta pooleks!“

Varblane ütles: „Ei hammusta!“

Hiir ütles: „Kui ei hammusta, siis ma lähen kaeban kuningale.“

Varblane ütles: „Mine, ma ei keela!“ Ja mõlemad läksid oma teed.

Hiir läks kuningale karule kaebama, et varblane sõi kõik nisuterad ära. Varblane läks jälle oma kuninga kotka juurde ja seletas sellele asjalugu. Kotkas ütles: „Kui nad tulevad sinu käest küsima, siis ära anna!“

Karu ja hiir tulid varblase käest küsima: „Kas hammustad tera pooleks või mitte?“ Varblane ütles ikka: „Ei hammusta!“

Siis läks karul süda täis, ta läks kotka juurde ja ütles: „Kas sa ei saa varblast keelata! Ta sõi hiire eest kõik nisuterad ära!“

Kotkas ütles: „Ega ma juures ei seisnud, ei tea, kumb sõi!“ Karul sai süda täis, et kotkas talle vastu räägib, ja tõmbas küüntega kotkal kogu naha maha. Kotkas jäigi sinna, nagu oleks nülitud.

Üks mees oli jahil ning nägi, et kotkas istus kivi peal, ja tahtis teda ära tappa. Kotkas hakkas paluma: „Ära tapa mind! Mis sulle minust saab? Vii mind koju ja sööda mulle iga päev üks nuumhärg! Siis saan ma terveks ja aitan sind.“ Mees ei tapnud kotkast ja viis ta koju, andis iga päev nuumhärja. Söötis kotkale kõik nuumhärjad.

Siis ütles naine: „Vii ta metsa ja tapa ära! Sa söötsid talle kõik nuumhärjad, aga terveks ta ei saanud!“ Mees võttis kotka jalgu pidi selga ja viis metsa, tahtis ära tappa. Siis hakkab kotkas jälle paluma: „Ära tapa mind! Vii mind koju ja sööda mind üks nädal! Anna iga päev kasvõi üks hanigi! Siis ma saan terveks.“

Mees viis jälle kotka koju ja andis iga päev ühe nuumhane. Söötis talle kõik haned ära, kuid kotkas ei saanud terveks. Siis ütles naine: „Vii ta nüüd ometigi metsa ja tapa ära! Söötsid talle juba kõik härjad ja haned, aga terveks ta ikka ei saanud.“ Mees viis kotka jälle metsa ja tahtis ära tappa. Kotkas hakkas jälle meest paluma: „Ära tapa mind veel ära! Vii mind koju ja anna mulle iga päev kasvõi üks kanagi. Siis saan ma terveks.“ Mees mõtles: „Mul on palju kanu, viin ta veel sel korral koju. Saab mis saab!“

Viis koju ja andis iga päev ühe kana. Söötis talle kõik kanad ära, aga ikka ei saanud kotkas terveks. Siis ütles naine jälle: „Vii see kurivaim juba metsa ja tapa ta ära! Ta sõi kõik härjad, haned ja kanad ära.“ Mees viis kotka metsa ja ütles: „Nüüd küll ei jäta sind enam ellu!“ Kotkas ütles: „Kulla mehekene, jäta mind veel see kord elama! Vii mind koju ja anna kasvõi üks munagi päevas, vahest siiski paranen.“

Mehel läks meel haledaks ja viis kotka koju ja andis iga päev ühe muna. Naine küll pahandas kõvasti, aga mees ei teinud seda kuulmagi. Söötis kotkale kõik munad ära. Kotkas sai terveks, nahk oli jälle peal nagu ennegi.

Kotkas ütles mehele: „Istu mulle selga, ma viin sind maailma vaatama!“

Mees ütles: „Ma ei julge istuda, sa viskad mu maha või viid kuhugi väga kaugele ära, nii et ma ei oska ja ei jaksa tagasi tulla.“

Kotkas ütles: „Ära karda midagi, maha küll ei viska! Ja kui ma viin su kaugele, siis toon tagasi ka.“ Mees istus kotkale turja peale ja kotkas läks lendu.

Naine veel tagant tänitas: „Vaat kus on rumal, läheb oma kotkaga taevasse. Seda ta söötiski teda kogu aeg. Söötis talle kõik härjad ja haned, kanad ja munad ära, mulle ei jätnud midagi.“

Kotkas ütles: „Kulla naine, küll ta toob mitme võrra tagasi! Oota ja anna aega!“

Kotkas lendas mere kohal ja laskus alla. Mees hüüdis: „Ära mine alla, väga hirmus on!“ Kotkas ütles: „Mul oli siis niisama hirmus, kui sa mind metsa viisid.“

Kotkas lendas üle mere ja sealt veel edasi, kuni jõudis koju. Mõlemad läksid majja, seal elas kotkas oma perega. Kõigil oli hea meel, et kuningas tuli koju, ja küsisid: „Kus sa nii kaua olid? Me mõtlesime, et sa oled surnud.“ Kotkas ütles: „Muidu oleksin küll surnud, kui see mees ei oleks mu elu päästnud.“ Mehele anti süüa ja juua, mida ta aga soovis.

Siis andis kotkas mehele kuldmuna ja ütles: „See on õnnemuna, ma kingin selle sulle.“ See muna oli nartsu sisse mähitud ja kotkas ütles: „Ära sa enne vaata ega lahti võta, kui saad oma maa peale! Kui sa selle muna lahti võtad, siis tekib sinna ümber suur linn.“ Kotkas käskis mehel selga istuda ja hakkas tagasi tooma. Tõi mehe üle mere ja laskis ta maha, ütles: „Mine nüüd ise koju, ma lähen tagasi!“ Jättis mehega jumalaga ja lendas kodu poole.

Mees tuli ja hoidis muna kogu aeg peos ja mõtleb: „Peaks vaatama, milline see on. Vaat söötsin, söötsin kotkast, ta ei surnud ära. Sain isegi kuldse muna, aga peaks vaatama, võibolla ei olegi kuldne, võibolla on raudne või tinane.“

Mees võttis muna kätte, harutas nartsu seest lahti ja vaatas – kuldne muna, väga ilus, puha läigib. Tõstis pilgu üles ja vaatas: tema ümber on linn. Aga ta ei olnud veel oma maa peal. Ja siis tuli mehele korraga meelde, et kotkas ei lubanud enne vaadata kui oma maa peal, et kui vaatad, siis tekib ümber suur linn.

Mees mõtleb, et mis nüüd saab. Ja vaatab: kotkas lendab jälle tema juurde ja küsib: „Mida sa mõtled?“ Mees ütles: „Ma mõtlen sellest, mis nüüd saab – ma vaatasin muna ja tekkis suur linn. Aga see ei ole veel mu oma maa.“ Kotkas ütles: „Vot sa ei kuulanud seekord mu sõna, kuigi ma keelasin. Ma tulin sulle appi.“ Kotkas ütles: „Anna muna siia!“ Mees andis muna kotkale ja kotkas mähkis muna uuesti nartsu sisse. Korraga kadus linn ära ja kotkas andis muna jälle mehe kätte. Kotkas ütles: „Kui oma maa peale jõuad, siis võta lahti. Siis tekib suur linn ja sa saad kuningaks.“ Rahvas nägi, et oli linn ja kadus jällegi ära, et mis temp see oli.

Mees läks siis oma maa peale ja harutas muna lahti, tekkiski suur linn ja keset linna ilus loss ning tema oli ise seal sees naise ja lastega, uhked rõivad kõik seljas. Naine küsis: „Kuidas see tuli?“ Mees ütles: „Kotkas tegi nii selle eest, et me söötsime talle kõik härjad, haned, kanad ja munad.“ Mees võttis kuldse muna taskust välja ja näitas naisele: „Vaata, see tegi meile linna ja meid valitsejateks.“ Naine ütles: „Too siia, ma vaatan!“ Mees andis muna naise kätte ja linn kadus ära. Vaatavad, et on selles samas vanas tarekeses, kus varem elasid. Mees ütles: „Vaat, anna sulle vaadata! Anna mulle tagasi!“ Naine andis muna mehe kätte ja jälle tekkis samasugune linn. Mees vaatas, et seda muna ei või mujale panna ja kellelegi teisele anda, kui ainult enda käes hoida.

Mees hakkas naisega linnas elama, mees oli kuningas, naine proua. Seda muna hoidis mees kogu aeg taskus. Naine ei läbenud ja rääkis tuttavatele: „Mu mehel on selline muna.“ Ühel kuninga alamal oli kuninga peale süda täis ja ta tahtis seda muna ära varastada, aina otsis võimalust, kuidas saaks ära varastada. Ükskord läks kuningas järve äärde ja läks suplema. Too mees läks salaja, võttis taskust muna ära. Korraga kadus linn ära ja nad sattusid jälle sinnasamma majakesse elama, kus enne elasid. Siis sai mees aru, et keegi võttis muna ära. Sellepeale hakkas naine pahandama: „Miks sa ei hoidnud hoolsalt!“

Mees läks metsa, et raiuda üks ahjutäis puid. Läks teed mööda ja mõtles: „Ei tea, kus mu sõber kotkas ka on? Kui too tuleks appi ja ütleks, kuhu muna jäi.“ Korraga lendas kotkas talle ligi ja küsis: „Mis mure sul on?“ Mees seletas: „Läksin suplema ja keegi võttis mu muna ära ja nüüd elan jälle vaeselt oma väikeses tares.“ Kotkas ütles: „Ma tahan sind veel kord selle eest aidata, et sa mind aitasid ja kuulasid. Muna on ühe su alama käes, ta kandis su peale vihavaenu ja tema varastas selle ära. Ma annan sulle ühe kullast vitsakese, mine peksa teda sellega, siis ta annab sulle muna jälle tagasi.“ Mees võttis vitsakese ja läks peksis seda, kes tema muna oli ära võtnud. Siis see mees hakkas paluma: „Ära peksa enam!“ ja andis muna tagasi. Niipea kui võttis muna kätte, nii tekkis jälle suur linn, selline nagu ennegi oli.

Nüüd ei julgenud ta enam kuhugi suplema minna ega kuhugi muna jätta. Nad elasid linnas kuni surmani ja mees oli kuningaks. Kui kuningas ära suri, kadus linn ja kadus ka muna ära. Keegi ei tea, kuhu see jäi. Naine sattus jälle oma tarekesse elama selle eest, et ta käskis mehel kotka metsa viia ja ära tappa. Senikaua nägi ta head elu, kuni mees elas. Kotkas tahtis karule selle eest kätte maksta, et ta tõmbas tal naha seljast. Aga sellist aega ei tulnud kunagi. Sellest ajast saadik ei pidanud hiir enam varblasega sõprust.

If a fisherman goes fishing, put a pot on fire, if a hunter goes to forest, put a pot upside-down.

Kui kalamees läheb kalale, pane pada tulele, kui jahimees läheb metsa, pane pada kummuli.

He who wants to become a son-in-law, should have horse's patience and hare's feet.

One is of cat size but is made into bear size.

Kassi suurune on, karu suuruseks tehakse.