Christmas and New Year

Jõule kutsuti vanasti "talsepühi" – talvepühad. Jõulu nimi tuli hiljem kasutusele. Vanasti ei teadnud keegi jõuludest midagi, kõik kutsusid talsepühiks.

On Christmas morning, people got up early and took bread to the animals. The farm people – master and servants – had to eat all together at one table. When it became light, the older people brought in the Christmas straw.

Jõulupüha hommikul aeti vara üles, viidi loomadele leiba. Jõuluhommikul pidi talu rahvas kõik ühes lauas sööma. Kui valgeks läks, tõime jõuluõled sisse. Vanemad inimesed tõid.

On Christmas Eve, straw was brought in. We children had new clothes on, new leather shoes on our feet. We did not go to sleep in our beds, but threw ourselves on the straw. It was crushed extremely finely. Whoever wanted to brought new straw for the New Year.

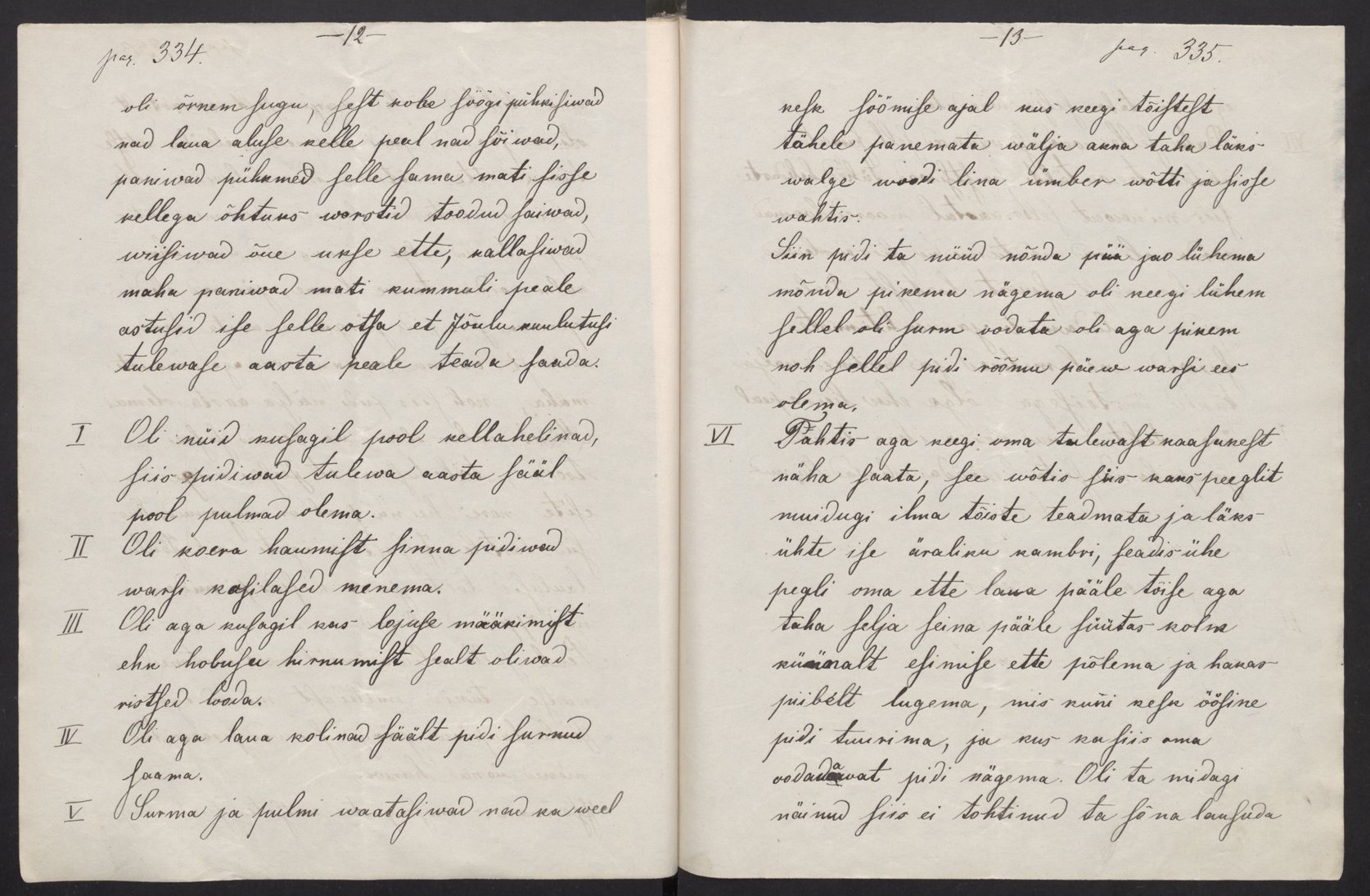

The passport kicking game was played in which straws were folded into knots to kick with – it was child's play.

The hostess sometimes brought straws herself, long hand threshed straws, and sometimes the maid also brought them.

Öled toodi sisse, õled jõululaupäeva õhtul. Meil lastel olid uued riided seljas, uued pastlad jalas. Voodisse ei mindud magama, õlgede peale heideti. Need olid siis nii peeneks tehtud et hirmus. Kes tahtis, tõi uueks aastaks uued õled.

Passi löödi. Õlgedest käänati kokku nuut ja lõid passi – laste mäng oli.

Perenaine vahest tõi ise õled, käsitsi pekstud pikad õled, vahest tõi tüdruk kah.

Two players are sitting facing each other on the floor in the tailor’s pose.

The first asks: “Where are you going?”

The second replies: “To Courland.”

The first: “What for there?”

The second: “To earn money.”

The first: “Show your passport!”

Now the second lies back and the first kicks him with the straw knot at the bottom. Thereafter the first lies back and the second sits up again and kicks likewise the first, etc.

Kaks mängijat istuvad vastastikku maas (põhus) – rätsepaistmes.

Esimene küsib: „Kuhu lähed?“

Teine vastab: „Kuramaale.“

Esimene: „Mis sinna?“

Teine: „Raha teenima.“

Esimene: „Näita passi!“

Seejärele kallutab teine ennast selja peale ja esimene lööb käes oleva õlenuustiga teise istekoha pihta. Selle järele kallutab esimene ennast selili ja teine tõuseb endisse asendisse ja lööb samuti esimesele jne.

Every Christmas Eve, the floor was washed clean. Straight, long straws were brought in, the children were frolicking there. Christmas sausage was cooked. The children were waiting for the evening. The Christmas tree was as it was, and everyone had a spruce, but not everyone had decorations. By the first holiday it was swept clean, and there was no straw for the New Year.

Igal jõululaupäeval pesti põrand puhtaks. Sirged pikad õled toodi, lapsed seal väherdasid. Keedeti jõuluvorsti. Lapsed ootasid õhtut. Jõulukuusk oli selline nagu oli. Kuusk oli küll igaühel, ehteid ei olnud igaühel. Esimeseks pühaks pühiti puhtaks, uueks aastaks ei olnud õlgi.

In some places, the master would open the door on Christmas Eve and shout out into the yard,

"Christmas, come inside!"

In other places, someone would go out the door in the evening and ask:

"Is Christmas allowed to come into the room?"

I don't know if the person who asked was dressed in disguised clothes or whatever.

Mõnes kohas avanud peremees jõulu õhtul ukse ja hüüdnud õue:

"Jõulud, tulge tuppa!"

Teisal jälle läinud keegi õhtul ukse taha välja ja küsinud:

"Kas on jõulul luba tuppa tulla?"

Ei tea, kas oli küsija moonutatud riides või kudas.

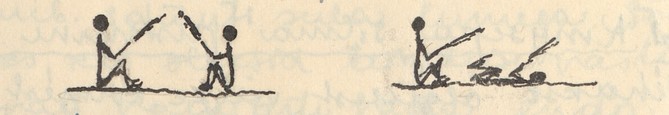

Five generations ago, there was no prayer house in Kastre-Peravalla, and the Christmas Eve sermon was held in the threshing room of Mäha farm, which was also the living room. Straw was brought to the floor, food for the oxen was put in a trough, and the oxen, who came home from the forest wet from hauling wood, were also placed in the living room to eat. The people gathered for a prayer meeting, sitting down on the straw floor to listen, and the sermon was delivered by Mäha Jakob, who had held the position of schoolmaster for 40 years, teaching children in the threshing room of his farm and preaching on Sundays and during the holidays.

So it also happened that people prayed on Christmas Eve in the room where the oxen fed themselves from the trough, because they had no warm place elsewhere.

Viis inimpõlve tagasi ei olnud Kastre-Peravallas veel palvemaja ning jõululaupäev peeti jutlust Mäha talu rehetarõn1, mis ka ühtlasi oli elutuba. Toodi õled põrandale, ka pandi härgade toit moldi, asetadi härjad, kes metsast puuveolt märjad koju tulid, ka elutuppa sööma. Rahvas kogus jõulu õhtul palve tunnile, istus õlgede pääle põrandale kuulama ja jutlust ütles Mäha Jakob, kes 40 aastat koolmeistri ametit pidas, oma talu rehetares õpetades lapsi ja pühade ajal, samuti pühapäevadel jutlust pidades.

Nii on siis ka ette tulnud, et rahvas jõululaupäeva õhta palvetas tuas, kus veohärjad molli pääl ennast toitsid, et neil mujal sooja ruumi ei olnud.

1 rehetares

"When beer was drunk on Christmas morning, was then some of the beer thrown into the hearth?"

"When the beer got good, it foamed, and the foam was blown off before drinking. That the clay floor wouldn't get wet and slippery, and the gift of God must not be put under the feet, so the foam was blown into the hearth before drinking."

"Did you start singing after drinking?"

“In the evening some of the younger ones sang too”.

At Christmas and New Year, food was put on the table so that the spirits would come. Afterwards, straw and hay were brought in. Children could play there.

"Kui jõuluhommikul õlut joodi. Kas siis koldesse osa visati?"

"Kui hea õlu sai, see vahutas, ja vahtu puhuti maha enne joomist, et savipõrand märjaks ega ligedaks ei saaks, ja Jumalaannet jalgade alla ei tohi lasta, siis puhuti vaht pealt koldesse, enne kui jooma hakati."

"Kas laulma kah hakati, peale joomist?"

"Õhtul ikka mõni noorem laulis kah!"

Jõululaupäeval ja vana-aastaõhtul pandi söök laua peale, et vaimud tulevad. Pärast toodi õled ja heinad sisse. Seal võisid lapsed mängida.

It was the gentler sex who were especially keen on such predictions, and immediately after the meal they wiped the top of the table on which they had eaten. They put the scraps in the same vessel with which the sausages had been brought for the evening. They then took the vessel outside and emptied it out by the front of the door. They overturned the vessel and sat on its bottom to find out the Christmas announcements for the coming year.

Iseäranis niisuguste katsete [ennustamiste] peale hagav1 oli õrnem sugu, sest kohe söögi [järel] pühkisivad nad laua aluse, kelle peal nad sõivad, panivad pühkmed selle sama mati2 sisse, kellega õhtuks vorstid toodud saivad, viisivad õue ukse ette, kallasivad maha, panivad mati kummuli peale, asusid ise selle otsa, et jõulu kuulutusi tulevase aasta peale teada saada.

1 agar

2 puunõu

On Christmas Eve, according to folk custom, the fire must be lit at night and the meal must be on the table because those relatives who have died, are supposed to go home to eat that night.

Jõululaupäeval peab rahvakombe järele öösel tuli põlema ja söök laual olema, sest omaksed, need kes surnd on, pidavat sel ööl kodu söömas käima.

For Christmas there was hay and for the New Year straw on the ground, and they slept on the hay. Sausages were cooked and the table was covered for the night so that the spirits would visit. Clean linen was put on the bed, but the people slept on the hay. They whisked themselves in the threshing room, as there was not such a separate sauna, especially in the house of the manor’s farmhands – they washed themselves in their own room, in the wooden trough.

Jõulust1 olid einad ja uuest aastast2 olid õled maas, heinte peal magati. Vorstid küpsetati ära ja laud kaeti ööseks, et vaimud pidid käima. Voodi pandi puhas pesu, aga oma inimesed magasid eintel. Vihtlesid rehetoas, ega niisukest sauna ei olnud; eriti moonamajas3 seda ei olnud, pesti oma toas, vanni sees.

1jõuluks

2 uueks aastaks

3 mõisatööliste majas

On New Year's Eve, straw is brought into the room. The straw-carrier enters the room with a sheaf, saying on the threshold:

"Hello, family here! Do you have permission for the New Year to come in?"

The answer is: "Hello, in the name of God, come yourself and bring the New Year."

Comment: The straw (or hay), brought inside for the winter holidays, was called the Christmas or New Year as if the sheaf itself were the personification of the holidays.

Vana-aasta õhtul tuuakse õlgi tuppa. Õlgede tooja astub vihuga tuppa, lävel üteldes:

"Tere, siit pere! Kas nääril luba tuppa tulla?"

Vastatakse: "Tere Jumala nimel Tule ise ja too näärid kaasa."

In the country, during the evening, straw is brought into the room so that a good spirit can sleep in the bed and will not bring misfortune during the year.

Õhtul tuuakse maal õled tuppa, et siis hää vaim saab voodis magada ja ei toob sel aastal õnnetusi.

On New Year's Eve, straw was brought into the room and all sorts of tricks were done. Sometimes they would string a horse's shaft bow to the ceiling and swing in it.

Vana-aasta õhtul toodi õled tuppa ja tehti siis igasuguseid tempe. Mõnikord kinnitati nööridega lae külge hobuse look ja siis kiiguti selles.

When I was still a girl, straw was brought into the room on New Year's Eve. Children frolicked on it and slept there too. On New Year's Eve, luck was poured from melted tin. After looking at its shadow, they tried to decipher the meaning of the image of this lump of tin and predict the future according to the image. After 12 o'clock at night, bread was brought to the animals.

Comment. Tin had been heated in a ladle and poured into water for telling the fortune.

Kui ma tütarlaps olin, siis toodi vana-aasta õhtul õlgi tuppa. Lapsed hullasid nende peal, ja seal magati ka. Vana-aasta õhtul valati õnne tinast. pärast varju pealt püüti mõistatada selle tinaklombi kujutise tähendust ja selle järgi ennustati tulevikku. Peale kella 12 öösi viidi loomadele leiba.

On this night, too, straw was brought in the old days, and then thrown carefully against the house’s ceiling and crossbars. If there was a lot of straw left hanging on the ceiling and the bars, the following summer good rye would grow.

Also, the farmer used to take a handful of each grain and throw it against the ceiling of the room saying: "God let our grain grow so long this year!"

At midnight they poured out good luck from the melted tin , poured from the ladle, and listened outside on an upturned sieve on the pile of sweepings. – Where the planks were clattering and rumbl ing, there would be a funeral that year; where a child's shriek of joy was heard, there would be a christening; where there was a cheer, there would be a wedding. On New Year’s Morning, bread was given to the horses and the livestock, and crosses were made on all the doors and thresholds with a burnt stick. On that day they hurried home from church, for whoever got home first would be the first to finish their work for the whole coming year.

Ka sellel õhtul olla enne vanasti õled sisse toodud, mida siis hoolega vastu tare lage ja parsi visatud. Kui siis hästi palju kõrsi lakke ja partele rippuma jäänud, siis kasvanud järgmisel suvel head rukkid.

Ka olla peremees igast viljast peotäie võtnud ja vastu toa lage visanud ja ütelnud: "Jumal lasku meie vilja sel aastal nii pikaks kasvada!"

Keskööl valatud tinast õnne ja kuulatud väljas pühkmehunniku otsas kummuli sõela peal – kus laudu kolistatud, seal tulla sel aastal matused; kus lapse karjumise rõõmu kuuldud, seal tulla ristsed; kus hõisatud, seal tulla pulmad. Uueaasta hommikul antud hobustele ja elajatele [=kariloomadele] leiba ja tehtud ka kõigi uste ja lävede peale peeruga ristid. Sellel päeval tõtatud kirikust õige kiiresti koju, sest kes kõige enne koju jõudnud, see olla ka kogu tuleva aasta jooksul oma tööd kõige enne jõudnud ära teha.