Animals

The wolf howls to his son on the shore of Lake Pühajärv: wow, wow!

The cubs reply: bow-kow, bow-kow, bow-kow!

Ellen Liiv: Where was that child when you were reading like that, on your lap?

Bertha Ilver: No matter, on my lap or anywhere. To hush.

Hunt ulub oma poega Pühajärve kalda peal: auu, auu!

Pojad teevad vastu: kiu-kau, kiu-kau, kiu-kau!

Ellen Liiv: Kus see laps sul oli, kui sa niiviisi lugesid, süles või?

Bertha Ilver: Ükskõik, süles või ükskõik kus. Nagu vaigistuseks.

She was an orphan girl and a suitor came to their place. She wanted him, but her mother, or actually her stepmother, mocked her and didn’t want him, of course… However, the suitor somehow succeeded to steal the desired girl.

And so the orphan started to live with this man, the suitor, and a child was born, was it a boy or a girl. The stepmother went there to the christening with her own daughter, and somehow the stepmother turned her stepdaughter into a wolf, replacing her with her own daughter. The wolf escaped. And the stepmother said: „You see, what a tramp! Look how she has left…“ [---] The child remained to be brought up by the daughter of this [evil stepmother]. But she herself left for the forest.

The father also had a servant, a babysitter. But the child was very restless. The daughter – and false mother – suckled the child but the breast was what it was. And the child didn’t stay long at her breast. The babysitter took the child on her lap and she understood everything; she realised that the daughter was not the real mother, and so she went to the forest and sang like this:

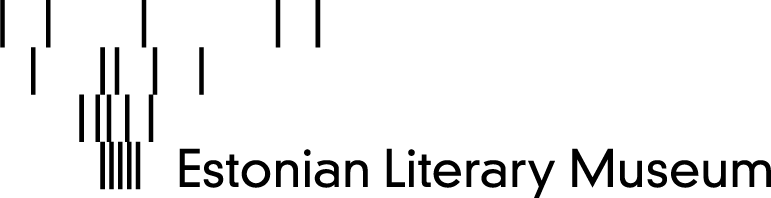

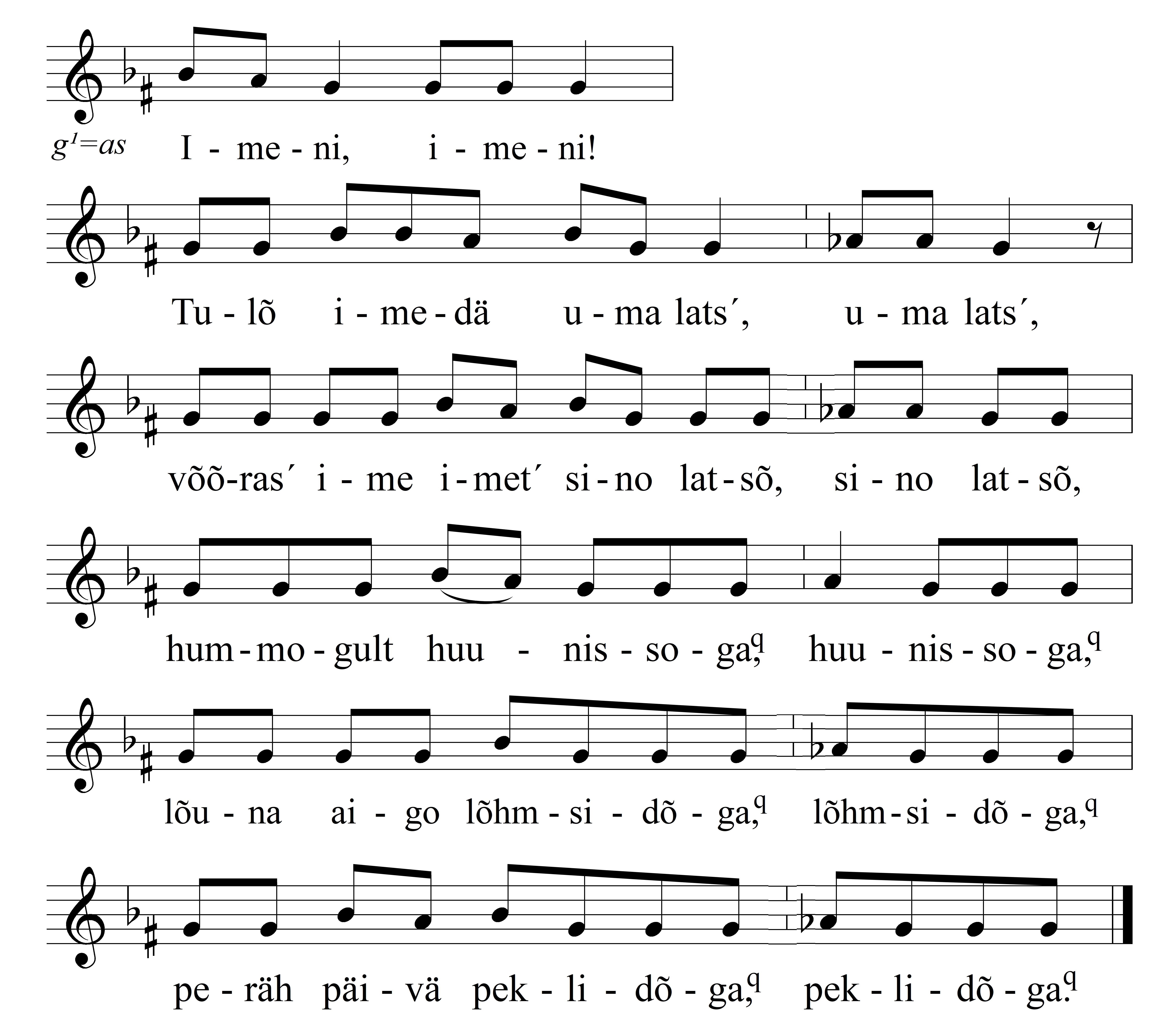

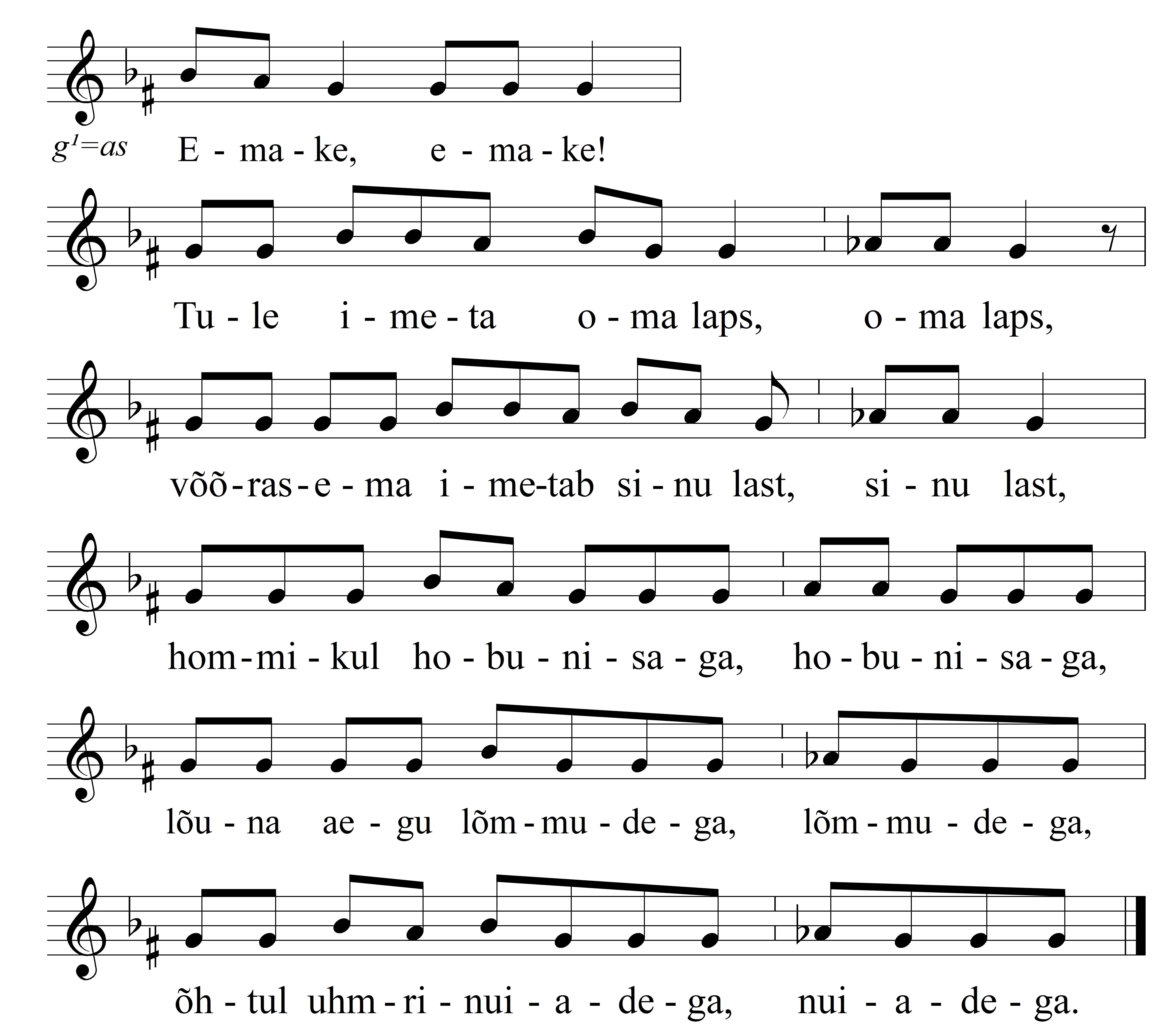

Mummy, mummy!

Come suckle your child!

The stepmother suckles your child,

By horse teats in the morning,

by mortar pestles in the evening,

by dry pine logs in the noon.1

And then the orphan – mother – came! In the old days it was said that she was wearing tar skin or wolf skin and that she threw it off. And she suckled the child and gave it back; she took her skin and went back to the forest.

But again the child didn’t stay at the breast of this devil on the second day. How could the baby accept this! So, the babysitter took the child again to the forest. But the man was also there and heard the babysitter… or he noticed that the babysitter went there with the child and sang again like this:

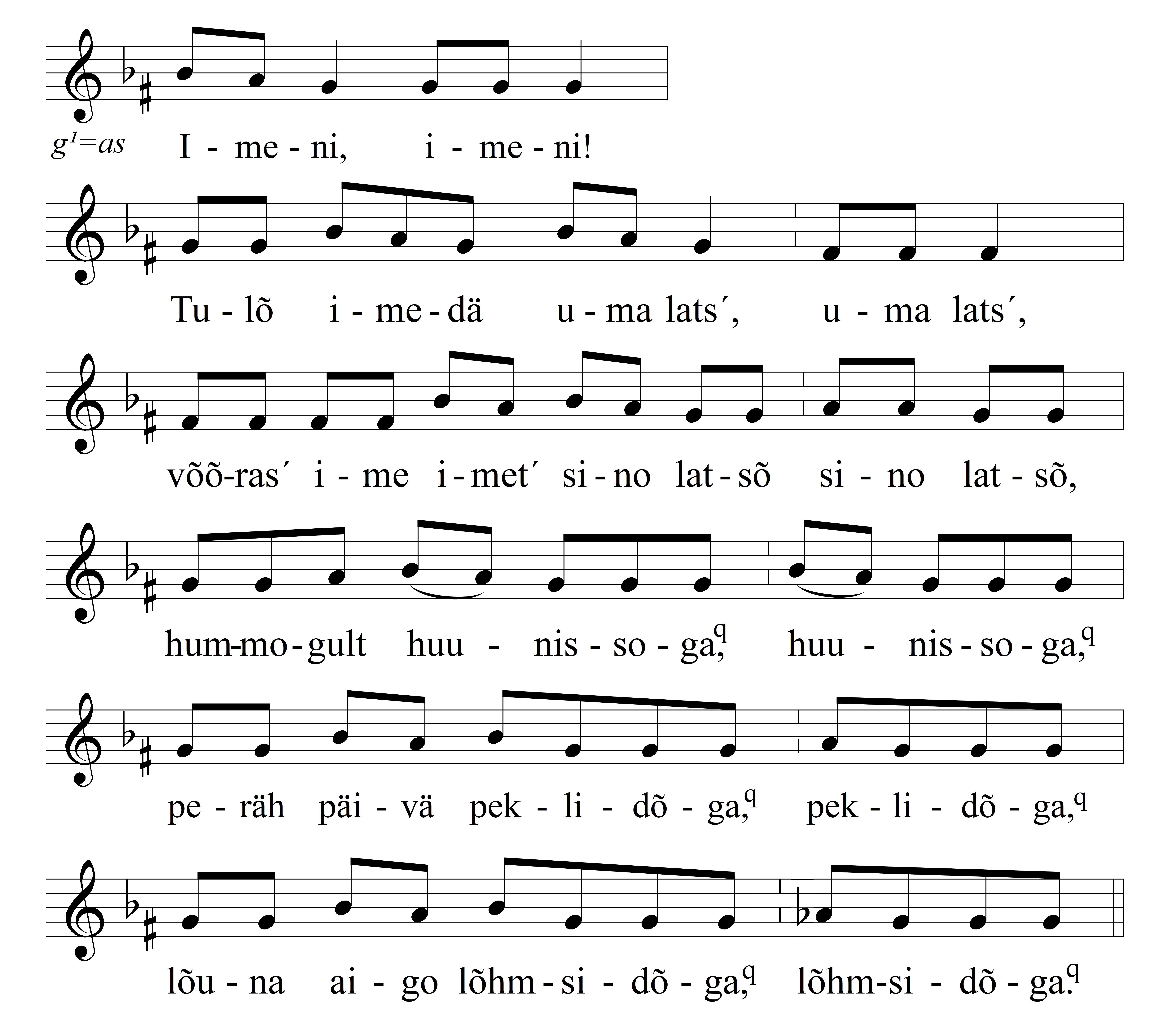

Mummy, mummy!

Come suckle your child!

The stepmother suckles your child,

By horse teats in the morning,

by dry pine logs in the noon,

by mortar pestles in the evening,

Yes, again the mother gave the child back to the babysitter. She herself pulled on the wolf skin and went back to the forest. The babysitter went home with the child.

The man then went to a sage, or witch. The latter instructed him: „Find out where she goes with the child and heat up a stone already there. See where she throws that wolf skin, and heat the stone up very, very well. When she throws off the skin and it catches fire, and she tries to escape, catch her and don’t let her go! Whatever she does don’t let her go! Finally, when she turns herself into a spindle, break it. Wrap it into a shawl and take it to the bed, and you will have your wife back.“

And this is what he did. He heated up a stone. The babysitter was singing there, and the mother came there again. He threw the skin on the stone and it caught fire. The mother wanted to escape but the man grabbed her and didn’t let her go. She turned herself into everything! The man was scared but he still didn’t let her go. Finally, she turned herself into a spindle. He broke it, wrapped it into a shawl and took it home. It became his wife again.

But the evil stepmother's daughter… I don’t remember what happened to her, or how she got killed. Maybe stones were brought to her and were placed in such a way that she died. And the man started to live with his wife again.

1There were special logs in the household, to be cut into splinters. In the comments of the other variants of the same fairy tale it has been said that the stepmother tried to make breasts out of birch bark or wood pieces.

Ta oli vaeslaps, ja sinna tuli kosilane. Tüdruk tahtis teda, aga ema, see tähendab võõrasema, siis muidugi pilkas teda ega tahtnud… Aga mees kuidagi varastas ta.

Ta hakkas selle mehega koos elama. Ja tal sündis ka laps, oli siis poisike või tütarlaps. Võõrasema läks oma tütrega sinna ristsetele. Ja võõrasema muutis ta kuidagi hundiks ja pani oma tütre sinna asemele. Ta põgenes ära, see hunt. Eks siis võõrasema ütleski et: „Näed, oli selline hulgus ja nõnda ta läkski…“ --- Lapseke jäi selle vanapagana [võõrasema] tütre kasvatada. Aga naine läks ära metsa.

Sel mehel oli võetud ka teenija, lapsehoidja. Aga lapseke oli väga püsimatu. Ta [vale ema] andis talle küll rinda mis ta andis, selline nagu see tema rind oligi. Aga laps ei püsinud rinna otsas. See hoidja võttis lapsekese sülle ja – ta teadis kõike, sai aru, et see pole õige ema – ja läks metsa äärde ja laulis seal:

Ja siis ta tuligi. Vanasti üteldi, tõrvanahk või hundinahk, mis tal seljas oli, selle viskas maha. Ja imetas lapse ära ja andis tagasi; võttis oma naha ja läks tagasi metsa.

Nõnda lapsekene teine päev jälle ei püsinud selle vanapagana rinna otsas. Kuidas ta saakski sellega leppida. Niisiis, lapsehoidja viis lapsekese jälle metsa äärde. Aga mees käis ka seal ja kuulis, et hoidja… või märkas, et hoidja läks lapsekesega sinna ja laulis nii:

Jah, [ema] andis siis lapse uuesti hoidja sülle. Ise tõmbas hundinaha selga, või soenaha, ja läks tagasi metsa. Hoidja läks lapsega koju.

Siis läks mees targa või nõia juurde. See õpetas: „Uuri järele, kuhu ta lapsega läheb, ja aja seal juba enne kivi kuumaks, uuri kuskohta ta täpselt selle naha viskab, ja aja seal kivi hästi, hästi kuumaks. Kui ta selle naha maha viskab ja nahk ära põleb ja ta tahab põgeneda, sa võta ta kinni ja ära lase enam lahti, ükspuha mis ta ka ei teeks, aga ära teda lahti lase. Aga lõpuks, kui ta moondab ennast kedervarreks, siis murra see katki, pane räti sisse ja vii voodisse, siis saad oma naise jälle tagasi.

Ja nii ta tegigi, ajas kivi kuumaks, lapsehoidja laulis seal – ja see tuli jälle. Viskas naha sinna kivi peale ja nahk läks põlema. Ta tahtis põgeneda, aga mees võttis ta kinni ega lasknud enam lahti. Ta moondas ennast kõigeks – mehel on küll hirm, aga lahti ka ei lase. Kõige lõpuks tegi ta end kedervarreks, mees murdis selle katki, pani räti sisse ja viis koju. Sellest sai uuesti naine.

Aga see vanapagana tütar, ma ei mäleta, mis temaga juhtus, kuidas ta surma sai. Kas toodi talle kive ja pandi nii, et ta sai surma. Ja mees hakkas jälle oma naisega elama.

[Voice.]

Anu Vissel: What was the voice?

Endel Kukk: The voice of the hare. A hare calls another hare like this in the spring, when it's mating time or running time, then he makes such a sound. Loud.

AV: Was this voice also made while herding?

AK: Sure, all the voices, of course.

[Heli.]

Anu Vissel: Mis hääl se nüüd oli siis?

Endel Kukk: Jänese hääl. Jänes kevadel niimoodi kutsub teist jänest, kui see paaritumise aeg ehk jooksuaeg on, siis ta teeb sellist häält. Kõvasti.

AV: Kas seda häält ka sai karjas tehtud siis?

AK: Sai, kõike, jah ikka.

Moose calf, moose bull, he-goat.

Põdravasikas, põdrapull, sokk.

Anu Korb: [How] were they lured to you?

Mihkel Prinken: Well, that's right, every animal comes and it happens at a certain time, but the moose is such an animal that you can call him to you most of the time. He comes to you both in winter and summer. The only keeping him away is the wind. It depends on where you are and where the animal is. If he happens to come against the wind, he will not come to you. But he still wants to meet the other. And mostly is possible to see him with the means of the voice.

Of course, it is during the evening meal, when the animal comes to eat. Then he is eating, and he downright listens, he talks. Is there another nearby? At times he makes calls, and then a bit anxiously listens if there is anybody somewhere. In case you can hear him - aha, there he is shouting! – answer him. They are like chatting

The other there goes: "Aah!"

And when you hear that he's "Aa"ing there, you answer here: "Oo!"

After a little while, he replies again: "Aah!"

After a while, you repeat again: "Oo!"

Then he starts coming. Then he comes.

"Aa!" – "Oo!" - "Aa!" – "Oo!"

And then some time will pass. Now that he already thinks he can get close to you, he makes one more noise and then listens to where are you now. He can tell right away by your voice how far you can be from him. He immediately measures the land with his ears.

But if you move there and spread your smell, you can't see him, he won't come.

But he has come, I have invited him to very close. If he happens to come well, he comes up to 4-5 meters away, comes to you, if he doesn't glimpse you. You have to hide so that he doesn't see. If he doesn't smell. If he can smell you, he won't come.

And so are other wild animals. If you sound right, you can always call them. Come, come! He, damned, does not come.

Mart Jallai: Let's make that calling sound!

MP: That sound was like what I was doing right now. That's the call. And the young animal has, when they are separated again, let's say a moose cow and a calf, then --- the calf whistles. It [the cow?] has it's special whistle, deeper than the other one. It sounds about like this:

[Whistling,]

About like this, such a whistle.

But the cow whistles, the cow has a deeper whistle. But they daw themselves together with a whistle. They are sometimes apart for certain periods of time. And the calf is not always with her. Then the calf is already bigger. It's parent is already getting it used to going alone and then again meeting in the forest, because... Sometimes it happens that they are very far apart, if either of them... let's say, for example, runs into dogs. It goes away, and then it is running for a certain amount of time, but it still comes back to this area to search the other. Then they whistle to each other. A calf and a cow always whistle when they want to get together. So they don't make that much louder noise, they still whistle when they want to get together.

But if you, a human, don't know anything about this whistle, you won't notice, so you can go without knowing anything about this whistle. You don't understand.

Anu Korb: [Kuidas] enda juurde neid peibutati?

Mihkel Prinken: Noh, see on niisukene asi et, egä loom tuleb juure ja see on teatud ajal, aga põdra on niisukene loom, et teda võib suurem jägu juure kutsuda alati. Tema kui talvel ja kui suvel, ta tuleb juure. Ainukene on see, mis ära oiab – tuul. Oleneb nii, et kuskohas sa oled ja kus see loom on. Kui juhtub, et ta vasta tuult tuleb, siis ta sulle juure ei tule. Aga kokku ta tahab ikkagi teisega saada. Ja näha võib teda suurem jagu alati saada hääle järgi.

No muidugi see on õhta süömise ajal, kui luom tuleb süöma. Siis tema süöb, ta kuulab kohe, tema ajab juttu. Kas on teist seal lähedal olemas? Tiatud aja tagant tieb äält, tema väiksel äristusel kuulab, kas on kuskil midagi. Juhul, kui sa ta ära kuuled – ahah, seal ta karjub! – vasta temale. Neil on nagu jutua'amine.

Teine tieb seal, tieb: "Aa!"

Ja kui sa kuuled, et tema seal aatab, sa tie siin vasta: "Oo!"

Ta tieb jälle vasta vähe a'a pärast: "Aa!"

Sa korda jälle vähe a'a pärast: "Oo!"

Siis akkab tema tulema. Siis ta tuleb.

"Aa!" – "Oo!" – "Aa!" – "Oo!"

Ja siis on ta teatud jagu aeg. Nüüd, kus ta juba arvab, et ta saab sinna ligi kohta, siis tieb korra viel äält ja siis kuulab – kus ta nüüd on? Märkab ära kohe selle ääle järele, kui kaugel sa olla võid, tähendab temast. Tema mõõdab maa otsekohe oma kõrvadega ära.

Aga kui sa seal liigud ja lõhna a'ad, siis sa teda näha ei saa, siis ta ei tule.

A ta on tuld, ma ole teda kutsunud päris juure. Kui ta trehvab easti tulema, siis tuleb kuni 4-5 mietri piale, tuleb sulle juure, kui ta sind ei silma. Sa pead niimoodi varjama, et ta ei näe. Kui ta lõhna ei tunne. Kui lõhna tunneb, siis ei tule.

Ja nii on metsloomad kõik. Ja ääldus on sul kääs, siis võid alati juure kutsu. Tule, tule! Teda, kurat, ei tule.

Mart Jallai: Teeme seda kutsumise äält!

MP: See ääl oli nii, nagu ma praegu tegin just. Niisamasugune ääl ta on. Ja noorel loomal on, kui nad jälle lahus on, ütleme lehm ja vasikas on, siis --- vasikas vilistab. Temal on oma vile, aga vile on jämedam kui teisel, umbes sarnane vile on:

[Vilistamine,]

Umbes sarnane, niisukene vile.

Aga lehm vilistab, lehma vile on jämedam. A nemad vilega võtavad endid kokku. Nad on teinekord teatud aegu lahus. Ja see vasikas ei ole alati tal juures. Siis on juba vasikas suurem. Tema vana nagu arjutab teda üksinda juba käima ja siis kokku saama metsas, sest et... Teinekord on niisukene juhus, on palju vahet, aga nüüd kumbki... kas ütleme, kas koerte ette sattub või. Läheb minema, aga siis ta küll jookseb oma teatud aja ära, aga ta tuleb ikka siia sellesse ümbrusesse taga otsima jälle. Siis vilega vilistavad. Vasikas ja lehm on alati vilega, tahavad kokku saada. Nii et nad palju niisukest valjumat äält ei tie, ikka vile on, kellega nad kokku saavad.

A kui sa seda vilest ju, inimene, ei tia, ei märka, sis sa võid käia, sa ei tia üldse sest vilest mitte midagi. Sa ei taipa.