Homestead

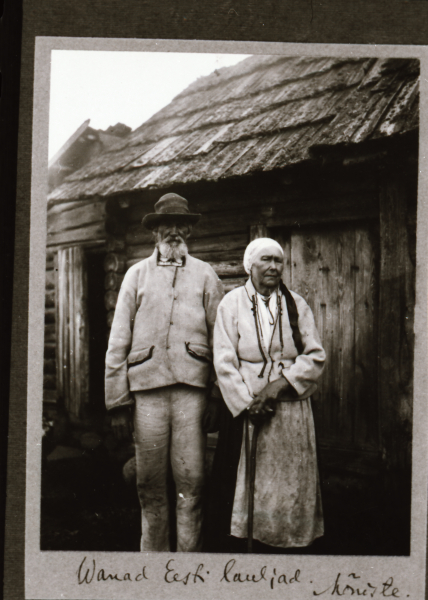

For rural Estonians, home was typically a farm, surrounded by neighbouring farms, fields, pastures, and groves. They did not call themselves Estonians, but rather maarahvas 'country people'. The homestead was their main place of work; in the old days, people lived in the log building with a huge oven, which also served as a place for drying and threshing grain in the autumn. In the yard there was also a stable, a barn, granaries, sheds, a sauna, and sometimes a summer kitchen as well. In Setomaa, the farm yard was closed and surrounded by a fence, and there was a separate building for the threshing floor. Elsewhere in Estonia during the 19th century, dwelling houses also began to be built separately from the threshing barn. The Estonian word for home is kodu, while koda is used for the temporary dwellings of nomadic people, and also for the hall. The word is very ancient, and similar words with the root kot or kod denote a building in Finno-Ugric and several other languages.

The farm was a world of its own, which had to enable sustainable living for many people. Ancient families tended to be large, with several generations living together, plus farmhands, maids and other helpers, lived together. However, their buildings were rather simple and small, because people lived as owned serfs until the early 1800s, and they were also required to work at the manor. The farm also included domestic animals, which also had to be looked after. During the cold winters peasants brought newborn animals into the dwelling house, because the barns were not heated,

The most mysterious building was a sauna, where the body was cleaned, diseases were treated and other magic done. Babies were born in the sauna and the deceased were prepared for their final journey; as if the sauna itself was the path between two worlds for souls to arrive and depart. So people had to be careful not to go to the sauna too late, because evil spirits could come there in the night. In the sauna, people were sweating and whisking, often accompanied by special magic spells, to become healthy and beautiful. The sauna was also a suitable place for other magic, for example to create a supernatural helper - a treasure carrier kratt or puuk.

The support of the home and its surroundings for a person was symbolized by local guardian spirits, called maa-ema, maa-isa, maa-jumal, or maa-vaim (Earth mother, father, god, or spirit). In domestic sphere, the fertility of the fields and animals was also not self-evident, but they all, together with the fertility fairies, had to be taken well care of. And so, dung was brought to the field for it's food, sacrifices were brought under a stone or in a sacred grove to the guardian of the homestead. The earth in the fields, the wells and the fire in the hearth - they all had to be treated with respect so as not to lose the favour of living nature. According to Oskar Loorits (1956), the idea of guardian spirits in the ground or under stones may have come from the veneration of the dead. In some regions the image of a fertility deity was kept at home and given food, such as Peko in Setomaa, or Tõnn in Pärnu county.

Farming skills included the ability to grow good crops not just for a few years, but for generations. Symbolic activities – feeding a fairy, making it’s statue, offering sacrifices or following calendar practices helped man to remember his part in the silent covenant with nature. Even seemingly irrational actions may have been important in shaping a person's thinking and values, on which the sustainability of life depended.

Everyday life was rather modest. Wealthy people were respected, but excessive greed for wealth in a community, where survival was not easy for all it’s members, might not have seemed so great. Mutual support was probably also considered important. The creators of folklore were often the poorer people, and their attitudes could influence the image of people in the community. The stories about supernatural treasure-bearers such as kratt, puuk, pisuhänd, varavedaja or others, indirectly expressed social control over human activities. A person who, under similar circumstances, was able to accumulate a significantly larger fortune, perhaps shared less with others and was on the way to separation from the community. The master had to give his soul for the supernatural helper, but the smarter ones knew how to avoid it.

The stories of the treasure carriers also reflect the idea that nature's resource is limited, it cannot be infinitely produced. According to beliefs, nothing in the world, neither wealth nor pests could be created or destroyed, but could be taken from one place to another. That's how stories about wealth carries arose, as well as teachings on how to get rid of cockroaches by taking them to neighbors or how to heal by sending diseases to birds.

Regilaul songs more often depict a woman's, rather than a man's, relationship with the home. The bright figures of the song’s images are born from the surroundings – a girl can feel like an egg or a flower in the grass. Feelings were expressed indirectly, through the representation of actions and through metaphors. The wedding songs during the bride's leaving ritual tell not only of the sad farewell of the family members, but also about how the whole house with its doors, windows and animals is left to cry for the daughter. In the new home, there would be a tour, where the bride gave gifts to important places, such as a well, a barn, a swing etc.

Home is the centre of human life and a model of the whole world. The folk tales reflect the idea that supernatural beings, like the Devil or a water spirit, also have their homes and family relationships. The water spirit keeps fish as domestic animals. This is not so inconsistent with modern science, because ants, for example, have complex living arrangements in their nests and keep aphids as pets. In the starry sky, the Estonian peasant saw the objects of everyday farm life - carts, rakes, flails, haystacks, and a plow ox, as well as an attacking wolf and a path of migratory birds.

Sources: Allikad: Oskar Loorits (1951), Kristiina Tiideberg (2009), ETY

Taive Särg