Insects

Fly, fly, ladybird!

Fly, fly, ladybird,

will the weather be fair tomorrow?

Whichever way it flies – toward the sun or away –

from that direction the good weather will come.

Endla Korila, 58 a. Otepää khk, Pilkuse k. Koguja Mall Hiiemäe 1982. RKM II 362, 325 (12). Foto: Tõstamaa khk, Ermistu k. Foto: Natali Ponetajev 2019. Inglise tõlge: Taive Särg..

Once, a gadfly died. A rabbit, a goat, a bear, a wolf, and a fox went to the gadfly's funeral. They all went to the gadfly's funeral on a dark, rainy night. They went and fell into a clay pit with the entire group. The pit was very deep, so none could get out.

The night ended, the day began, and they began terribly to want food. Fox said:

"Let's scream! We will eat the one who screams the highest."

Everyone started screaming, and the rabbit screamed the highest. The rabbit was eaten.

The next day, everyone started wanting to eat again. They said again:

"Let's scream! We will eat the one who screams the loudest."

Now the bear screamed the loudest, and they started eating the bear.

The fox was smart, and he knew how to arrange things so that he would be the last. He knew that the bear could not be left last; he was stronger. The bear was enough for them for a week.

They started wanting to eat again. Then the fox said:

"Let's scream! Whoever screams the loudest must be eaten."

The wolf screamed the loudest, and the fox ate the wolf. The fox alone remained. He found a bird's nest in the pit, with baby birds inside.

The fox wanted to eat the baby birds.

The bird began to beg: "Don't eat my babies!"

The fox said: "Carry the pit full of brushwood, so I can get out."

The bird felt sorry for her babies. She toiled for months until the pit was filled. The fox jumped to the edge of the pit and ran into the forest. The baby birds survived.

Ükskord suri parm ära. Parmu matustele läksid jänes, kits, karu, hunt ja rebane. Nad kõik läksid pimedal vihmasel ööl parmu matustele. Läksid, läksid, kukkusid kogu seltskonnaga saviauku. Auk oli väga sügav, nii et ükski ei saanud välja.

Öö lõppes, päev algas ja nad hakkasid hirmsasti süüa tahtma. Rebane ütles:

„Hakkame karjuma! Kes kisab kõige kiledama häälega, selle sööme ära.“

Kõik hakkasid karjuma ja kõige kiledama häälega karjus jänes. Jänes söödi ära.

Järgmisel päeval hakkasid kõik jälle süüa tahtma. Ütlesid jälle:

„Hakkame karjuma. Kes kõige valjemini karjub, tolle sööme ära.“

Nüüd karjus karu kõige kõvemini ja nad hakkasid karu sööma.

Rebane oli tark, ta oskas asju nii korraldada, et tema jääks kõige viimaseks. Ta teadis, et karu ei või viimaseks jätta, ta on tugevam. Karust jätkus neile nädalaks ajaks.

Hakkasid jälle süüa tahtma. Siis ütles rebane:

„Hakkame karjuma! Kes kõige kõvemini karjub, too tuleb ära süüa.“

Hunt karjus kõige kõvemini ja rebane sõi hundi ära. Rebane üksi jäi järele. Ta leidis augu pervest linnupesa, mille sees olid linnupojad. Rebane tahtis linnupoegi ära süüa.

Lind hakkas paluma: „Ära söö mu poegi ära!“

Rebane ütles: „Kanna mulle augutäis risu, et ma välja saaksin.“

Linnul oli oma poegadest kahju. Ta nägi mitu kuud vaeva, kuni sai augu täis. Rebane hüppas augu äärele ja jooksis metsa. Linnupojad jäid ellu.

August Jakobson „Sääsk ja hobune“ ja „Ämblik ja vähk“ raamatust „Ööbik ja vaskuss“.

Kuula siit:

https://vikerraadio.err.ee/837631/ohtujutt-saask-ja-hobune-amblik-ja-vahk

One day a horse was out grazing in the field when a mosquito flew up to him. "Don't you see me?" the mosquito asked, seeing that the horse did not notice him.

"I see you now," the horse replied. The mosquito looked over the horse—he looked at his tail, his back, his neck and at both his ears, one after the other. He looked and he shook his head.

"You're terribly big, my friend, aren't you!" said he.

"Well, yes, I'm not what you'd call small, agreed the horse.

"I am much smaller than you."

"You are indeed!"

"And you must be strong, too?"

"Strong enough."

"I don't suppose a fly could get the better of you, could it?"

"Certainly not!"

"Nor a horse-fly?"

"Nor a horse-fly."

"Nor even a gad-fly?"

"No. Nor even a gad-fly."

The mosquito was pleased. "The horse is strong but I’m even stronger," thought he, and, sticking out his chest, he said:

"You may be big and strong, Horse, but we mosquitoes are stronger still. We need only light into you, and you 11 be done for. We'll win hands down!"

"No, you won’t!" said the horse.

"Yes, we will!" "No!" "Yes!"

They went on like that for an hour and then another, but neither would let the other have the last word.

"It's no use arguing," the horse said at last. We can have it out between us and see who wins!

"Yes, let’s do that!" the mosquito agreed. He rose from the horse's back where he had been sitting and called in a piping voice: "Hey, there, mosquitoes, fly here!"

And at this so many mosquitoes came flying toward him as cannot be imagined! From a birch wood they flew, and from a spruce grove, from the swamps, and the pond, and the river, and they all flew straight at the horse. They settled all over him and clung to his body, and the horse asked: "Well, are all of you here now?"

"Yes, all!" replied the first mosquito who was a bully if there ever was one.

"And has each found a place for himself?"

"Yes!"

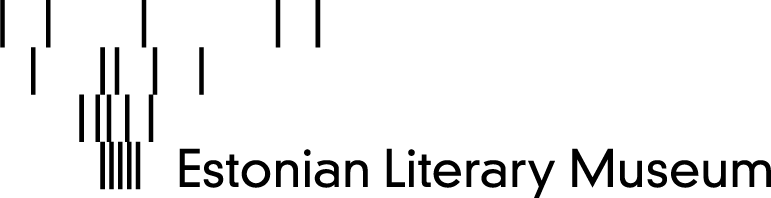

"Then hold on fast!" said the horse.

He flung himself down on his back, his hoofs sticking up in the air, and began rolling from side to side, and in less than a minute he had squashed all the mosquitoes. Of the whole mighty host only one little soldier was left alive, and even his wings were grazed; and, apart from him, the bully who had been sitting some distance away from the rest. That is always the way with bullies: they start a fight and then steal off and keep out of it. The little soldier who had only just managed to fly away from the horse now flew up to the bully, and, addressing him as if he were a general, reported:

"The horse is dead. Killed on the spot! Had we had only four more men we might have clung to his hoofs and skinned him."

"Good work!" said the bully, and off he flew hurriedly to the forest in order to tell the bugs and the gnats of the victory. For this was no joke!

The mosquitoes had vanquished a horse, so surely their tribe was the mightiest of all the tribes on earth!

Hobune sõi koplis, sääsk tuli lennates alt luha poolt. Hobune ei pannud sääske tähele ja sääsk küsis: “Külamees, kas sa mind ei näegi?” “Nüüd näen küll,” vastas hobune. Sääsk vaatas hobust väga tähelepanelikult - vaatas saba, vaatas selga, vaatas kapju, vaatas jalgu, vaatas keha, vaatas kõrvu. Väärutas imestades pead ja ütles: “Oi, oi, oled ikka, vennas, suur küll.”

“Olen, olen suur,” noogutas hobune.

“Sa oled ju, kaim, suurem minustki.”

“Olen, olen suurem sinuski.”

“Jõudu on sul kah vist päris palju?” küsis sääsk.

“No on palju, no on palju,” vastas hobune.

“Ega kärbsed tee sulle vist häda midagi?”

“Ei-noh, kärbsed küll mulle midagi häda ei tee.”

“Sõgelasedki vist... ei saa sinu vastu?”

“Ei-noh, sõgelased küll minu vastu ei saa.”

“Ega ole ju paremat palka parmudegagi?”

“Kus sa sellega, neh - ega ole paremat palka parmudegagi.”

Nüüd ajas sääsk rinna ette, uhkustas:

“Ole sa suur, mis sa oled, ole sa tugev nagu tahad - sääserahvas käib sust üle nagu poleks sind olemaski olnud!”

“Ei käi, ei käi!” ütles hobune.

“Käib, no käib!” jäi sääsk kindlaks.

Vaidlesid nõnda hobune ja sääsk tunni, vaidlesid teise - kumbki ei andnud järele. Kuni hobune viimaks arvas:

“Mis seal ilma asjata tülitseda ja tühja tuult tallata - katsume jõudu!”

“Õige, õige, katsume jõudu jah,” nõustus sääsk, tõusis lendu ja hüüdis heleda häälega: “Meie mehed - kähku kokku! Meie mehed, kähku kokku!”

Oi, oi, oi, kus siis hakkas sääski lagedale lendama! Tuli neid kaasikust ja tuli neid kuusikust; ilmus neid laantest ja ilmus neid rabadest; kihutas neid kohale soodest ja kihutas neid kohale sonnidest. Ja igaüks, kes aga pärale jõudis, asus kohe hobusele kallale! Kui kedagi enam tulemas polnud, vaatas hobune üle õla ja küsis: “Kas kõik on siin?”

“Kõik siin, kõik siin!” vastas pealik-sääsk.

“Ja kõik ju tugevasti tööl kah?” küsis hobune.

“Kõik tööl, kõik tööl!” vastas pealik-sääsk.

Hobune laskis enda nüüd pikali, hakkas kõvasti püherdama. Püherdas, püherdas, püherdas, ega jätnudki enne, kui sääskede vägi surnud oli. Ainult üks soldat-sääsk pääses eluga. Tõusis vaeseke oma valutavate tiibade varal kuidagiviisi õhku, lendas pealik-sääse juurde, lõi kannad kopsudes kokku ja teatas:

“Pikali saime vaenlase! Oleks meil veel neli meest olnud, kes oleksid hobust jalust kinni hoidnud - kõik seadsin juba valmis, tahtsin just nahka hakata võtma.”

“Tubli, tubli!” kiitis pealik-sääsk ja kihutas tuhatnelja metsa teistele putukatele ja matikatele rõõmusõnumit teatama - sääserahvas võitis hobuse enda, sääserahvas on tänasest päevast peale kõige vägevam rahvas terves maailmas!”

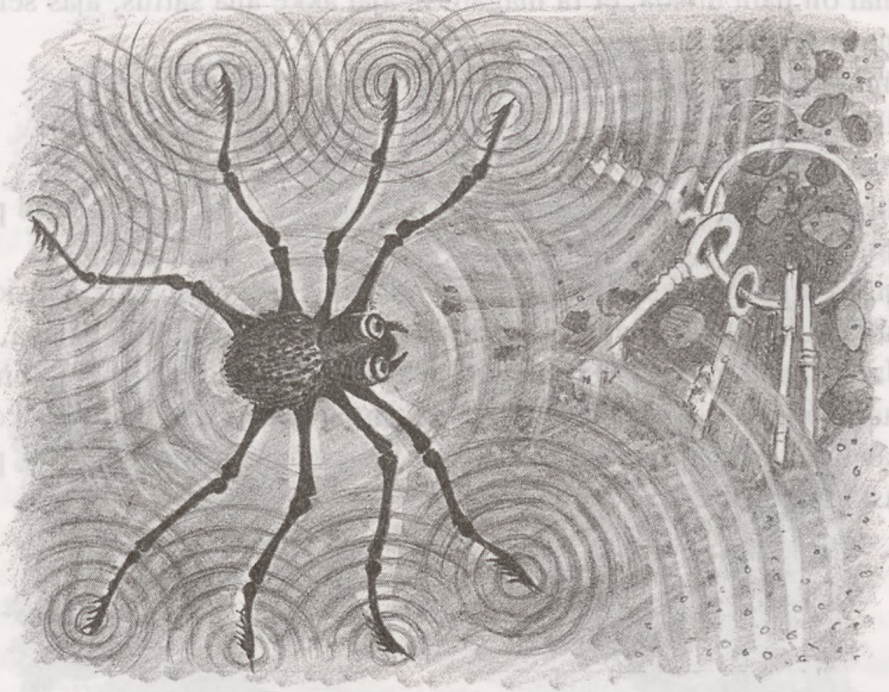

Once, during a drought that had burned the fields bare, the Forest Father was busy and rushing about, trying to give water to flowers, grass, bushes, and trees. In his haste, he lost the keys to his house. He searched and searched but could not find them anywhere. Finally, he decided to check the open plains and wandered through them, crisscrossing in every direction. Suddenly, he spotted a lake sparkling in the sunlight. Across the lake’s surface ran a gray grey spider on its long legs.

The Forest Father called out to the spider:

“Dear neighbour, why are you running around like that?”

The spider stopped and answered kindly:

“I am searching for a precious necklace that my great-great-great-grandmother lost two years ago on Midsummer’s Eve. Tomorrow is my younger daughter’s wedding, and I must give her the necklace; otherwise, a great misfortune will befall our family.”

“By any chance, have you seen my keys while searching for your necklace?” asked the Forest Father.

“Why, yes, I have,” the spider replied. “They’re right here at the bottom of the lake, in the deepest spot.”

The Forest Father thanked the helpful guide, and looked into the water, but with his old eyes, he could not see a thing. Finally, he called out, asking if any of the lake’s inhabitants could help him. The Forest Father’s plea was heard by old Uncle Crayfish, who was resting in his burrow beneath the shore. He was in a foul mood, poked his whiskers out of the burrow, and grumbled bitterly:

“Are your eyes on your back that you can’t see your own keys?”

The Forest Father said nothing at first. But once he had retrieved his keys with the help of a perch and gifted the fish an even finer coat than before, he tapped the lake’s edge with his cane and called out to the rude crayfish:

“For speaking to me like that, may your eyes be moved to your back!”

To the small, kind spider, the Forest Father gave a large ball of silk thread, from which the spider now weaves its webs and traps. Since then, the spider’s life has become much easier—it stretches out its webs, lays down to rests, and never lacks prey. The poor crayfish, however, now wanders backwards through the water, often feeling the pangs of an empty stomach.

Kord, kui põud oli põllud paljaks põletanud, oli Metsaisal rohkesti tööd ning tegemist, et lilledele ja rohule, põõsastele ja puudele juua anda. Selle suure tõttamise juures kaotas ta oma maja võtmed. Otsis ja otsis – ei leidnud neid aga kuskilt. Viimaks mõtles, et vaatab korraks ringi ka lagedal maal, ja hulkus sellegi läbi küll risti, küll põiki. Ning näeb korraga – päikesepaistel särab järv, mööda järvepinda jookseb ringi pikkade koibadega hall ämblik.

Metsaisa küsis ämblikult:

“Kulla külamees, mis sa seal sedasi kihutad?”

Ämblik peatus, vastas lahkesti:

“Otsin üht kallist kaelaehet, mille mu vana-vana-vana-ema tunamullu jaanilaupäeva öösel ära kaotas. Homme on mu noorema tütre pulmad ja ma pean selle kaelaehte temale kinkima, sest muidu tabab meie suguseltsi suur õnnetus.”

“Ega sa ei ole juhtunud oma kaelaehet otsides ka minu võtmeid nägema?”

küsis Metsaisa.

“Miks ei ole, olen küll,” vastas ämblik. “Need on siinsamas järve põhjas,

kõige sügavamas paigas.”

Metsaisa tänas lahket juhatajat, vaatas vette, ei seletanud seal aga oma vanade silmadega midagi. Ning hüüdis viimaks, et kas keegi sealsetest elanikest oleks nii hea ja aitaks teda ivake. Metsaisa palvet kuulis vana vähionu, kes puhkas parajasti oma kaldaaluses urus. Ta oli väga halvas tujus, ajas vuntsid urust välja ja torises südame täiega:

“Kas sinu enda silmad on selja taga, et sa oma võtmeid ei näe?”

Metsaisa ei vastanud esialgu midagi. Kui ta oma võtmed viimaks ahvena abil oli kätte saanud ja sellele senisest veelgi kenama vammuse kinkinud, koputas ta aga kepiga vastu järvekallast ja hüüdis ninakale vähile:

“Et sa, va toriseja, mulle nõndaviisi vastasid, mingu sinu enda silmad selja taha.”

Väikesele lahkele ämblikule andis ta aga suure kera siidniiti, millest see koob endale nüüd võrke ja püüniseid. Sellest saadik on äbliku elu hoopis kergem - tõmbab võrgud-püünised üles, heidab ise puhkama, saagist pole puudus kunagi. Vähk vaeseke rändab aga oma rändamisi vees tagurpidi ja peab tundma tühja kõhtu üsnagi tihti.