Trees and shrubs

Back in the old days, there lived an unspeakably rich and evil manor lord. He forced the people of his parish to do heavy labour both night and day, and would ceaselessly find fault with the workers for quite insignificant things. In addition to his great wealth, he had two sons and a daughter. When the girl had come of age, suitors came calling on her, but her stingy father said he wouldn’t give his daughter to anyone other than the type of man he himself was: rich and stingy and a big penny-pincher. What a sorry state of affairs!

At long last, a strange, unknown gentleman came courting her; he was warmly received. You could tell from the suitor’s clothing that he was a rich man, and when he placed a gold, jewelled ring on his betrothed’s finger as he bid her farewell, everyone’s joy knew no bounds, neither, however, did anyone start inquiring as to where the suitor was from. Then began preparations for a grand wedding, the day of which also arrived before long. The wedding had arrived, the guests were merry and gathered around the drinking tables, but they were still missing one thing: the groom hadn’t come. At long last, the groom also showed up, wearing dazzling clothes, seated in a six-horse carriage, and the wedding guests welcomed him gaily. The bride was merry and the wedding went on and on. At last, all the wedding guests were exhausted and drifted off to sleep from their fatigue.

When everyone was already sleeping, the groom said to his bride: “My dear wife, we will leave now, because we may not stay here another day; I have many great things to attend to at home and must be there before sunrise.” The bride did protest at first, but when the carriage rolled up to the doors at dawn, they both dressed and left without telling the others. The wedding guests were certainly sad when they awoke that morning, but there was nothing they could do. When the carriage reached the shore of the sea at sunrise, they rowed across it to the opposite shore. There, the young couple entered a majestic house that glittered with gold and pearls. The house held more beauty than it needed. The young bride had never seen such a sight with her own eyes before. She went to rest, but when she woke up, she could no longer find her husband at home. Two girls came to dress her: she asked them about her husband, too, but they weren’t able to utter an O or an A about it. When the young bride couldn’t get any clear details about her husband, who vanished from home every morning and returned only late each night, she secretly started keeping an eye on him.

One morning, she observed her husband get out of bed, turn himself into a snake, and disappear beneath the bed. The young bride froze as stiff as a tree in shock when she saw this. She thought about the frightful sight that whole day, and when her husband returned home that night, she asked him about it. The man didn’t want to say anything, but when the woman just wouldn’t give up, he finally explained: “I am the king of the sea serpents and must look over my kingdom every day and go to rule my subjects!” The woman wore a satisfied look, but great dread and fear filled her heart. They carried on living like that for many, many more good years. They already had three children, too.

One day, the woman came to her husband and requested that he allow her to go visit her parents. This wasn’t at all to the man’s liking, but he handed the woman a spindle of tow and said: “When you have spun this tow, then you may go on your merry way and see your parents!” This promise raised the woman’s spirits and she started spinning briskly, but soon saw that her joy had been premature, since although she spun the tow for nights and days on end, the spindle didn’t shrink in the least. She started weeping in misery. While she wept, a little grey man entered the room, comforted her, and said very kindly: “When you start spinning again, then shake the spindle hard!” The woman followed the old man’s advice and instruction, and lo and behold: tiny worms tumbled out like rain, the spindle started to shrink, and it finally ran out.

Now, the woman was overjoyed, because she could go to her long-missed homeland to see her parents and relatives. The boat had already been pushed into the sea for the journey. She held her three children close and with her husband’s help, they soon reached the opposite shore of the sea. The woman stepped on land with her children, but the man remained sitting in the boat and said: “I will wait here until you return. When you arrive, call me by saying:

Bring the boat, bring it about,

to gentle mother, to the kids!

If you call out those words and do not see me, then call out:

Little wave, row, reach,

show me sea foam bloody!

And if the sea then starts to foam, you will know that I have met my death in the deep currents!” The woman then left with her children. When she reached her father’s house, they were received with great joy. She didn’t speak a word about her life or her husband, though her relatives and friends pried incessantly. But then, they asked the children. The children told their uncle their father’s story. The uncle and other relatives plotted to divorce her from him, and decided to kill the man. What was said was done. Unbeknownst to the woman, they went to the edge of the sea and summoned the man:

“Bring the boat, bring it about,

to gentle mother, to the kids!”

The man came, and they seized and killed him. When the woman went to the sea and summoned her husband with the familiar words the next morning, despite her parents and relatives forbidding her from doing so, he did not appear. Then, the woman said:

“Little wave, row, reach,

show me sea foam bloody!”

When she spoke these words, the sea started foaming dreadfully. Now, the woman knew her husband had died. She began lamenting her husband dreadfully.

The grey man came to her and asked: “Hear, woman – what is your trouble? Can I perhaps help you again?” “Dear old man, my wish would be to become a tree: a good tree who is of use to the coming generation and who benefits others – and my children must be together with me!” The grey old man took his cane, tapped it three times against the woman’s head, and did the same to the children, who had come with their mother. And can you imagine what happened then! Suddenly, a beautiful, straight birch was standing before him. The woman grew into a birch tree, and her children grew into the bark around her. That is why the birch has three-layered bark to this day: first the inner bark, then the top white bark, and thirdly the one that flutters in the breeze and must endure hardship. That is the very youngest child – all because he was careless and revealed his parents’ secrets. That is how the birch tree came into this world.

Vanal ajal elanud üks väga ütlemata rikas ja kuri mõisahärra. Ta sundis oma valla rahvast öösel ja päeval raskele tööle ning nurises ühtelugu üsna tühja asja pärast tööliste üle. Peale suure rikkuse oli tal ka kaks poega ja üks tütar. Kui tütar juba täisealiseks oli saanud, tulid talle kosilased, aga ihnus isa ütles, et ei anna oma tütart kellelegi muule kui üksnes niisugusele, nagu ta ise on: rikas ja ihnus ning kange kokkuhoidja. Hea lugu küll!

Viimaks ometi tuli üks võõras tundmata härra kosja; teda võeti rõõmuga vastu. Riietest oli aru saada, et kosilane rikas mees on, ja kui ta jumalaga jättes pruudile kalliskividega kuldsõrmuse sõrme pistis, oli kõikide rõõm otsata ega küsitud pikemalt kosilase asupaiga järele. Siis algas kõva pulmade vastu valmistamine, mis peagi ka kätte jõudis. Pulm oli koos, rahvas oli rõõmus joomalaudade ümber, aga veel puudus neil midagi – peigmees ei olnud tulnud. Viimaks ilmus ka hiilgavates riietes peigmees kuue hobuse tõllaga ja pulmalised võtsid ta rõõmuga vastu. Pruut oli rõõmus ja pulm kestis ühtelugu edasi. Viimaks jäid kõik pulmalised rammetumaks ja uinusid väsimuse ja une kätte magama.

Kui kõik juba uinusid, ütles peigmees mõrsjale: „Armas abikaasa, teeme nüüd minekut, sest teiseks päevaks ei või me siia jääda; mul on kodus väga suuri talitusi, et enne päevatõusu kodus pean olema.” Mõrsja pani küll esiotsa vastu, aga kui koiduvalgel tõld ukse ette vuras, panid mõlemad end riidesse ja sõitsid ilma teiste teadmata minema. Pulmalised olid hommikul küll kurvad, kui üles ärkasid, aga ei võinud sinna midagi parata. Kui tõld päevatõusu ajal mere kaldale jõudis, siis sõudsid nad sealt laevaga üle mere teise poole kaldale. Seal astus noorpaar uhkesse majasse, mis kulla ja pärlite käes säras. Ilu oli majas rohkem kui tarvis. Noor mõrsja ei olnud veel oma elu sees niisugust oma silmaga näinud. Väsimusest heitis ta puhkama, aga kui ta üles ärkas, ei leidnud ta enam meest kodust. Kaks tüdrukut tulid teda riidesse panema; ta küsis ka nende käest oma mehe järele, aga need ei teadnud ka u-d ega a-d vastata. Kui noor mõrsja oma mehe üle selgust ei saanud, kes iga hommiku kodust ära kadus ja alles õhtu hilja koju tuli, hakkas ta salaja tema järele valvama.

Ühel hommikul nägi ta, kuidas mees voodist välja tuli, muutis ennast maoks ja kadus ära voodi alla. Noor mõrsja ehmatas seda nähes puukangeks. Ta mõtles kogu päeva selle hirmsa loo üle järele ja kui mees õhtu koju tuli, päris seda asjalugu järele. Mees ei tahtnud midagi sellest rääkida, aga kui naine sugugi järele ei andnud, seletas ta viimaks: „Ma olen meremadude kuningas ja pean oma riiki iga päev vaatamas ja oma alamate üle valitsemas käima!” Naine jäi küll rahule, aga tema südames oli suur mure ja kartus. Niiviisi elasid nad mitu ja mitu head aastat edasi. Neil oli ka juba kolm last.

Ükskord astus naine selle palvega mehe ette, et lubaks teda oma vanemaid vaatama minna. Mehele ei olnud see palve sugugi meele järele, aga ta andis ühe koonla naise kätte ja ütles: „Kui selle koonla oled ära kedranud, siis võid rõõmuga oma vanemaid vaatama minna!” Naine rõõmustas mehe lubaduse üle ja hakkas kibedasti ketrama, aga varsti nägi, et tema rõõm oli olnud enneaegu, sest kuigi ta küll ööd kui päevad ketras, ei vähenenud koonal sugugi. Ta hakkas haledasti nutma. Kui ta nuttis, astus üks hall mehike tuppa, trööstis teda ja ütles väga lahkelt: „Kui sa jälle ketrama hakkad, siis raputa koonalt kõvasti!” Naine tegi vanakese õpetuse ja nõu järele ning vaata imet, peenikesi usse sadas kui vihma maha ja koonal hakkas vähenema ja lõppes viimaks otsa.

Nüüd oli naine rõõmus, sest nüüd võis ta kaua igatsetud isamaale minna oma vanemate ja sugulaste juurde. Paat oli teele minemiseks juba merre lastud. Ta võttis oma kolm last ligi ja mehe abiga jõudsid nad peagi teisele poole mere kaldale. Naine astus oma lastega maale, aga mees jäi paati istuma ja ütles: „Ma ootan teid siin tagasitulekuni. Kui siia jõuate, siis hüüdke mind:

"Too paati, tuleta paati,

hella ema, laste vastu!"

Kui te aga nõnda olete hüüdnud ja mind ei näe, siis hüüdke:

"Lainekene, sõua, jõua,

näita mul vahtugi verine!

Ja kui siis meri vahutama hakkab, siis teadke, et ma vetevoogudes surma olen leidnud!”

Naine läks nüüd lastega minema. Kui ta oma isakoju jõudis, võeti neid suure rõõmuga vastu. Oma elust ja mehest ei rääkinud ta ühtainust sõnagi, kuigi küll sugulased ja sõbrad järelejätmata pärisid. Siis küsisid nad aga laste käest. Lapsed rääkisid oma onule, kuidas nende isaga lugu on. Onu ja teised sugulased pidasid nõu naist tast lahutada ja võtsid nõuks ta ära tappa. Mis mõeldud, sai tehtud. Nad läksid ilma naise teadmata mere äärde ja kutsusid meest:

„Too paati, tuleta paati,

hella ema, laste vastu!”

Mees tuligi, nad võtsid ta kinni ja tapsid ära. Kui naine teisel hommikul vanemate ja sugulaste keelust hoolimata mere äärde läks ja tuttava sõn aga oma meest kutsus, ei ilmunud teda mitte. Siis lausus naine:

„Lainekene, sõua, jõua,

näita mul vahtugi verine!”

Kui ta oli nii ütelnud, hakkas meri hirmsasti vahutama. Nüüd teadis naine, et tema mees surma oli saanud. Ta hakkas oma mehe järgi hirmsasti ahastama.

Üks hall mehike tuli tema juurde ja küsis: „Kuule naine, mis sul viga on? Kas ehk mina võiksin sind jälle aidata?” – „Armas vanake, minu soov oleks puuks saada, üheks heaks puuks, kellest tuleva põlve rahvale kasu kasvab ja tulu tõuseb – ja minu lapsed peavad minuga ühes olema!” Vana hall mees võttis oma kepi, lõi sellega kolm korda naisele pähe, niisamuti ka lastele, kes emaga ühes olid tulnud. Ja vaata imet, mis siis sündis! Korraga seisis tema ees ilus sirge kask. Naine kasvas kasepuuks ja lapsed kasvasid kooreks tema ümber. Sellepärast on kasel veel tänapäevani kolmekordne koor: esiteks alumine koor, teiseks pealmine valge koor ja kolmandaks see, mis tuule käes lipendab ja vaeva nägema peab. See on kõige noorem laps – sellepärast, et ta kergemeelne oli ja oma vanemate saladused avaldas. Nõnda oli kasepuu ilma sündinud.

Once upon a time there was a man and a woman. They had three daughters: the youngest; the eldest, and the middle one, of course. The berry forest was close to their home and they decided to pick berries there.

The youngest daughter was diligent and would do any work. As they arrived in the berry forest, they saw there were shrivelled strawberries growing on the clearing floor. The eldest and the middle daughter did not want to pick these strawberries and they said: „Why pick these tiny things! We had better go and find the places with bigger berries.“

The youngest daughter said: „I am not going. I will pick these here. You go if you want to!“ and she stayed there alone to pick the little strawberries. The middle and the eldest daughter walked and walked around the forest but it was still early [early summer] and the bigger strawberries were still white. So, they did not get anything. The evening was arriving and they returned to the clearing where the youngest daughter was still picking. Her stomach was full and her basket was full. Having seen this, the eldest daughter became jealous and, considering it with the middle sister behind the tree, said: „Let’s kill her!“ So they did.

There was a lane running through the forest and they buried her near this lane. But how to remember her grave? They planted a birch tree thereon. The lane was for the merchants, who travelled from one town to another.

So, the sisters went home. They shared the younger sister’s strawberries between them. The mother and father asked: „Where is the youngest daughter?“ „We didn’t see her at all. We went to the forest together but she was picking on her own and we were on our own. We know nothing about her.“ They denied it all.

Mother’s and father’s hearts were aching, as it was already getting dark. They heard the merchants coming and did not want to make a fuss about their daughter missing from home.

After a while, some merchants came to the village and rode along the same lane where the birch tree was planted nearby. One of the merchants was a young boy and he chopped down the birch tree and made a harp (kannel) from it. He made the harp’s box [it was made from one tree] and the harp started to play without any strings, and it played like this:

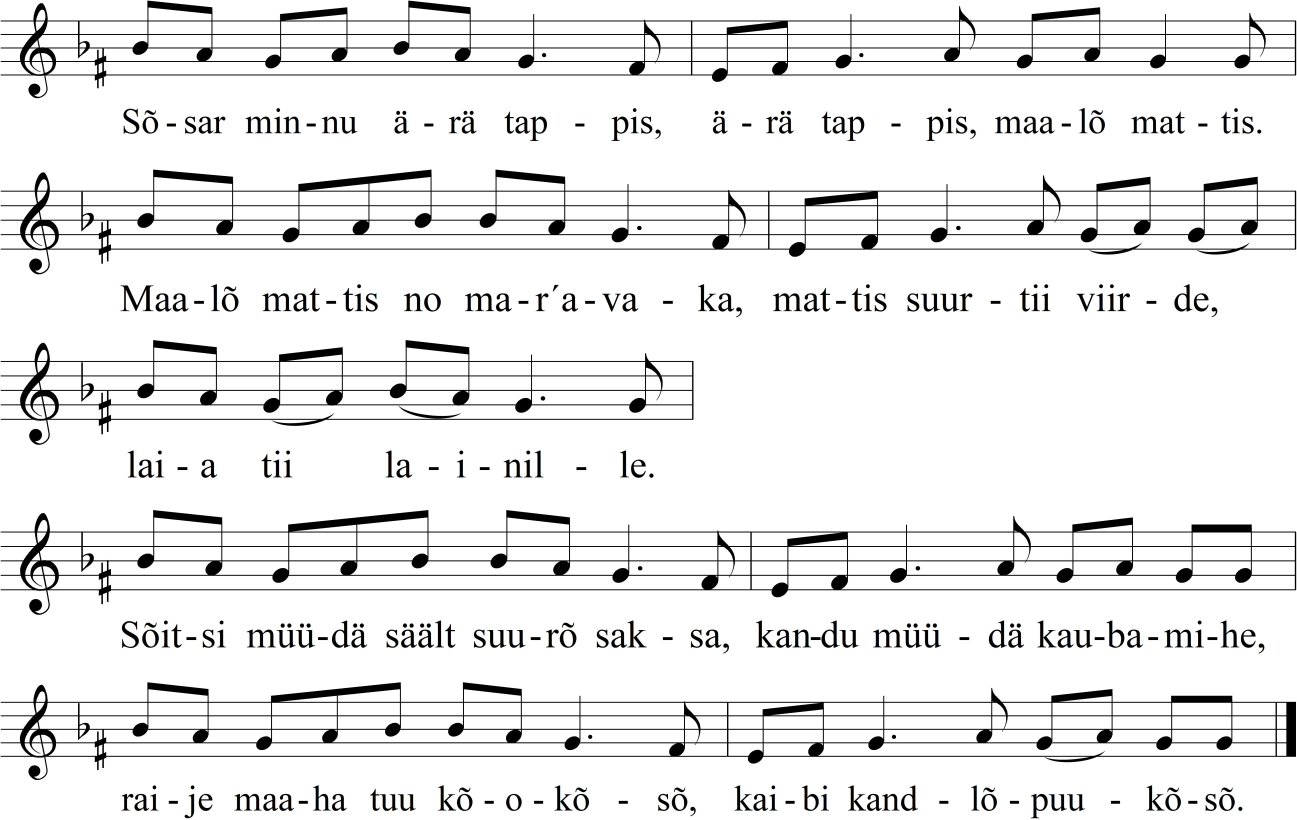

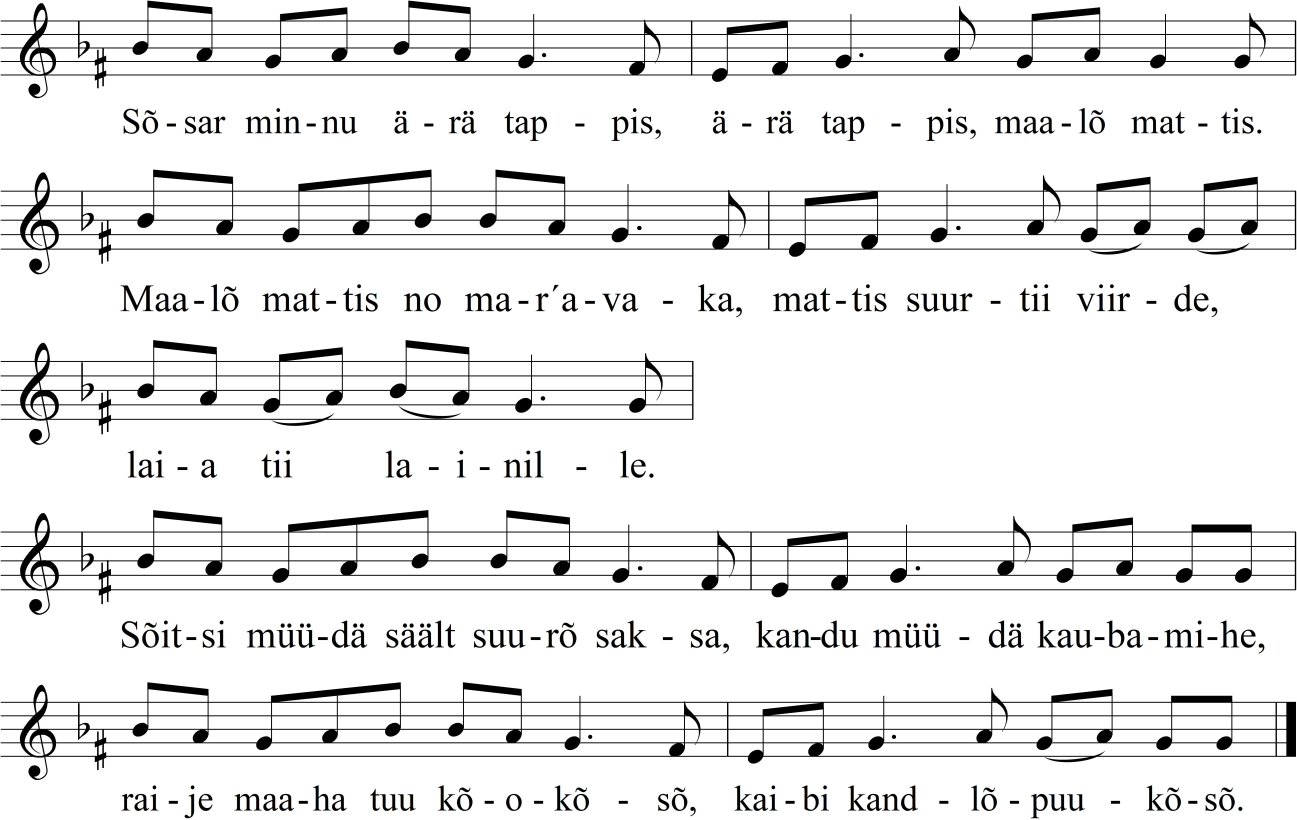

Sister killed me, sister buried me into the earth.

She buried my berry basket, next to the great lane, on the waves of the wide lane.

Great gentlemen passed through, merchants rode through.

They chopped down a birch tree, they dug up a harp tree.

The evening was arriving and merchants went to seek a lodging house in the village. The harp kept singing like that all the time. As there were many merchants, they split themselves between the farms. The merchant with the harp stayed with the family whose youngest daughter was missing. The mother and father heard this harp play and they asked: „Could we have this harp, too.“ The merchant gave it to them and the harp kept playing the same way. As it was given over to the sisters, the harp no longer played.

This is how it was found out that they had killed their sister.

Elasid eit ja taat. Neil oli kolm tütart: noorem, vanem ja muidugi ka keskmine. Marjamets asus nende kodu lähedal ja nad otsustasid sinna marjule minna.

Noorem tütar oli usin ja sai iga tööga toime. Kolmekesi marjule jõudes nägid nad, et raiesmikul kasvasid kidurad maasikad. Vanem ja keskmine tütar ei tahtnud neid maasikaid korjata ja ütlesid, et: „Oh, mis me ikka neid korjame, me läheme otsime parem, kus on priskemad marjad.”

Noorem tütar ütles: „Ei mina enam otsima lähe, mina korjan siin, minge teie pealegi!” ja jäi üksi raiesmikule pisikesi maasikaid korjama. Keskmine ja vanem tütar käisid ja käisid mööda metsa, aga oli varajane aeg ja maasikad olid veel valged. Nii nad ei saanudki mitte midagi.

Õhtu hakkas juba kätte jõudma ning nad läksid tagasi raiesmikule, kus noorem tütar ikka veel korjas. Temal oli kõht täis ja korv täis. Vanem tütar läks seda nähes kadedaks ja jäi keskmisega puu taha aru pidama ning ütles:

„Tapame ta ära!” Tapsidki noorema ära. Metsast viis läbi tee ja nad matsid ta tee veerde. Selleks, et meeles pidada, kus sõsara haud on, istutasid sinna peale kasepuu. Koju jõudes küsisid isa emaga:

„Kus noorem tütar on?”

„Aga meie ei näinudki teda. Metsa läksime küll ühes, aga tema korjas omaette ja meie omaette. Meie ei tea temast midagi.”

Salgasid kõik maha. Isal-emal jäigi süda valutama.

Mõne aja pärast tulid külla kaupmehed ja sõitsid seda sama teed mööda, kuhu veerde oli kasepuu istutatud. Üks kaupmees oli noorem poiss ja tema raius kase maha ning tegi endale kandlepuu. (Noh, vanasti olid targad mehed.) Kannel hakkas ilma keelteta mängima ja mängis nii:

Õhtu hakkas kätte jõudma ja kaupmehed läksid küla peale öömaja otsima. Kannel kogu aeg laulis niimoodi. Kuna kaupmehi oli palju, siis nad jagasid endid talude vahel ära. Kandlega kaupmees sai öömajale selle pererahva juurde, kust noorem tütar oli ära kadunud. Isa emaga kuulsid kandlemängu ning palusid:

„Andke mulle ka toda kannelt”.

Kaupmees andis ja kannel mängis niimoodi isa käes ja ema käes. Anti kannel sõsarate kätte, aga kannel nende käes ei mänginud. Ja nii saadigi teada, et nemad oma sõsara on ära tapnud.

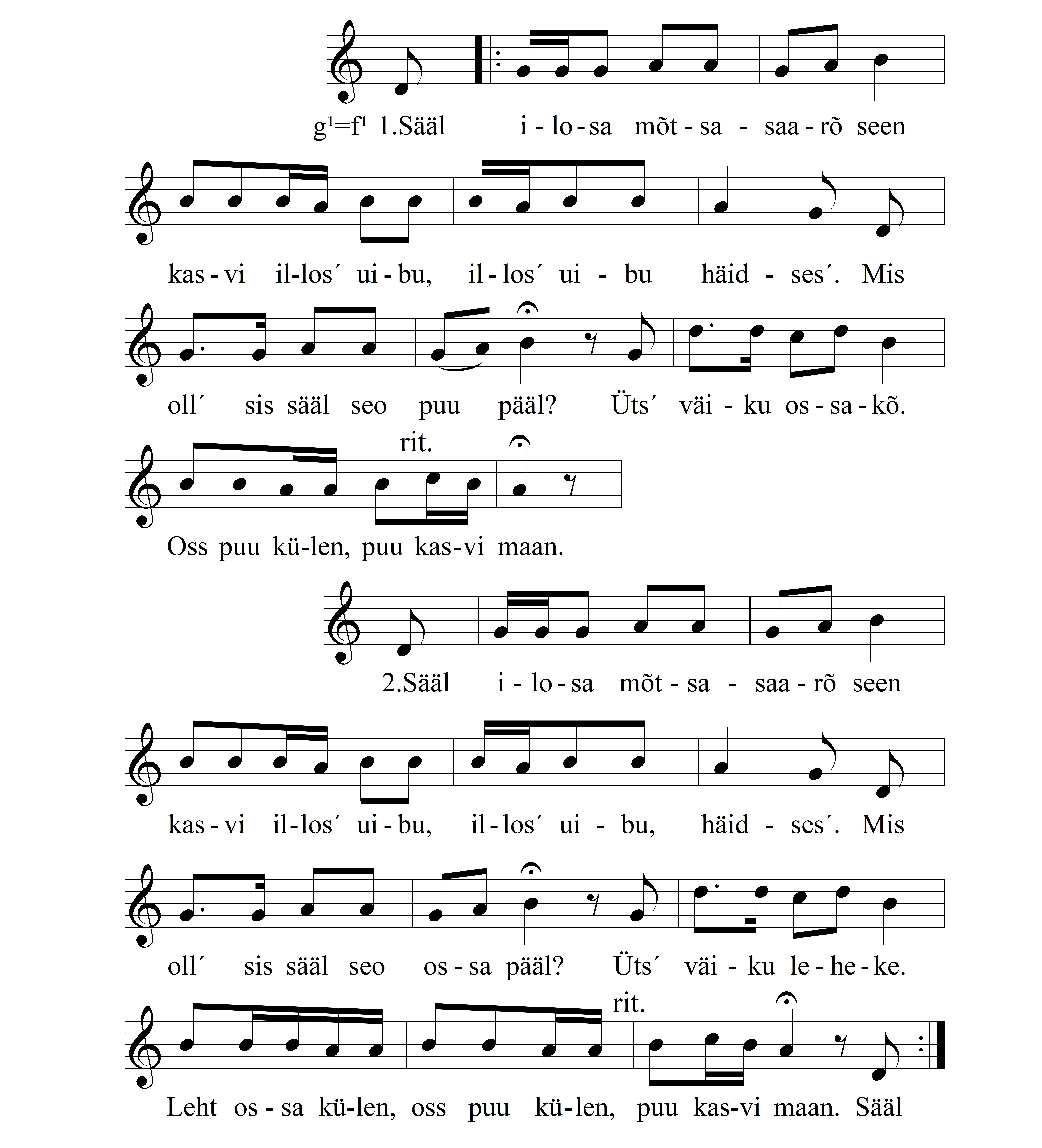

1. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was was on that tree?

One small branch.

A branch on the tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

2. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was on that branch?

One small leaf.

A leaf on a branch,

a branch on the tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

3. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was on that leaf?

One small nest.

A nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on the tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

4. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was inside that nest?

One small egg.

Egg inside the nest,

nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on a tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

5. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was inside that egg?

One little bird.

A bird inside an egg,

egg inside the nest,

nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on a tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

6. There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

So what was in that bird's mouth?

A little song.

A song in the mouth of the bird,

bird inside the egg,

egg inside the nest,

nest on a leaf,

a leaf on a branch,

a branch on a tree,

the tree grew on the ground.

There inside a beautiful forest island

a beautiful apple tree grew, a beautiful apple tree blossomed.

1. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle puu peal?

Üks väike oksake.

Oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

2. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle oksa peal?

Üks väike leheke.

Leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

3. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle lehe peal?

Üks väike pesake.

Pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

4. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle pesa sees?

Üks väike munake.

Muna pesa sees,

pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

5. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle muna sees?

Üks väike linnuke.

Lind muna sees,

muna pesa sees,

pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

6. Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.

Mis oli siis seal selle linnu suus?

Üks väike lauluke.

Laul linnu suus,

lind muna sees,

muna pesa sees,

pesa lehe peal,

leht oksa küljes,

oks puu küljes,

puu kasvas maas.

Seal ilusa metsasaare sees

kasvas ilus uibu, ilus uibu õitses.